This is an Eval Central archive copy, find the original at depictdatastudio.com.

Visualizing data in charts, graphs, dashboards, and infographics is one of the most powerful strategies for getting your numbers out of your spreadsheets and into real-world conversations.

But it can be overwhelming to get started with data visualization. Does data visualization leave you feeling like the numbers are about to topple over on you??

If so, this step-by-step data visualization guide is for you! I’ll walk you through the data visualization design process so you know what to do first, second, and third as you transform your spreadsheets into stories.

Step 1: Understand Your Audience

Wait! Don’t start making graphs on your computer! First, we have to do some planning. A little bit of up-front planning will save you hours of blood, sweat, and tears in the long run.

First, you need to analyze your audience. Who, exactly, is going to be using the data to make decisions?

Analyzing your audience is the least linear of all the thinking steps in the design process. Rather than relying on computer software or your programming skills, this step involves the most valuable computer of all—your brain.

Who is Your Audience?

Your audience should be your primary consideration. A chart designed for a group of foundation program officers will not be appropriate for a group of high school principals, and vice versa. List all your audience types on a piece of paper, or a whiteboard, or in a spreadsheet, or even on the back of a napkin. Share the list with your colleagues and make sure you’re on the same page. Have you reached consensus about who you’re targeting with your data?

What’s Your Audience’s Numeracy Level?

Do they enjoy or fear data? Unless you’re designing charts for a group of economists or statisticians, you can usually leave out details like the effect size, power analysis, and margin of error. Laypeople are often more interested in practical significance (the “so what?” and implications of findings) than in statistical significance.

What’s Your Audience’s Data Visualization Familiarity Level?

If they’re brand new to dataviz, stick with the traditional charts like pie charts, bar charts, and line charts—otherwise they’ll spend more timing ooh-ing and aah-ing over the chart’s novelty than paying attention to the information contained in the chart.

How Much Time Does Your Audience Have?

Little time or interest: Simple static chart. Lots of time and interest: Interactive charts.

What Types of Decisions Does Your Audience Make?

What information do they need? What information do they already have? What information are they expecting? How will your chart(s) add value for them? If you can’t think of how your chart will add value for the readers, don’t make one. Every chart needs a purpose and so what?

How Much Precision is Necessary?

As the data visualization designer, you have the freedom (and responsibility) to select how much precision is necessary. Your selection should be well thought-out and intentional. Your decision plays out in two ways: the chart type you select, and how you label the data points.

When selecting chart types, remember that some charts are better than others in displaying precision. For example, charts that rely on angles and area to show differences, like pie charts, are for communicating general patterns. Charts that rely on length to show differences, like bar charts, are for communicating specific details.

How Many Decimal Places Are Necessary?

A related decision is how exact your data labels will be. Will you include decimal places? How many?

In most scenarios, you can safely round your decimal places to the nearest whole number. Your audience is rarely using the tenths, hundredths, or thousandths place to make decisions.

Are My Viewers Expecting a Story?

Think about whether your audience is expecting you to tell a story with data–or not.

Step 2: Choose the Right Chart

It takes a while to understand all the different chart types and to pick the best one for your desired takeaway message. There are tons of great graphs to choose from!

Consult a Chart Chooser

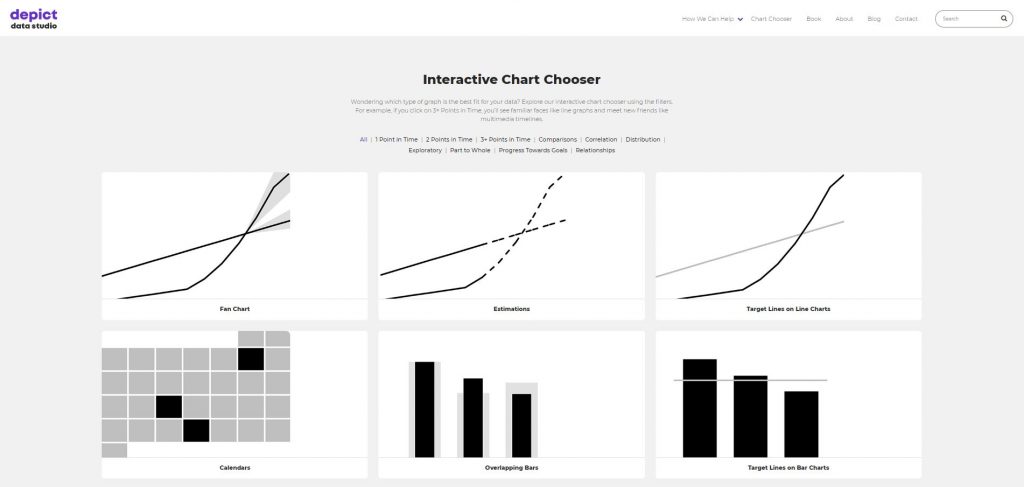

My interactive Chart Chooser includes dozens of chart types, resources, tutorials, and templates.

New to Dataviz? Start with Classic Chart Types

If you’re not sure which chart to use, stick with classics like the bar chart to compare categories and the line chart to visualize how things change over time. These charts will be “right” most of the time, so they’re a safe bet.

Use Pie Charts Sparingly

Contrary to popular belief, pie charts are not evil and don’t have to be avoided altogether. I have seven guidelines for using pie charts and donuts. In this pie chart makeover, I show you how to transform a 3D pie chart with way too many slices into a storytelling bar chart with icons:

Getting Comfortable with Dataviz? Branch Out and Try Other Chart Types

Once you’ve mastered the classic chart types, you can play around with less-familiar chart types like bubble charts, bullet charts, dot plots, heat maps, scatter plots, slope graphs, social network maps, tree maps, waterfall charts, and more.

Surround Yourself with Positive Inspiration

Surround yourself with great graphs so you can expand your worldview of what’s possible with data visualization. I suggest following top-notch data journalism teams like @PostGraphics, @NYTgraphics, and @WSJgraphics.

You can even create a physical or digital library of great graphs. For example, you might print full-page, full-color charts and tape them near your desk. Surrounding myself with a variety of chart types, all of which have been used in different reports and for different groups of people, helps me create brand new charts easily. All I do is glance up at my gallery, and then I quickly figure out which chart is best for my new situation.

Dive Into Your Dataset with Exploratory Data Visualization Techniques

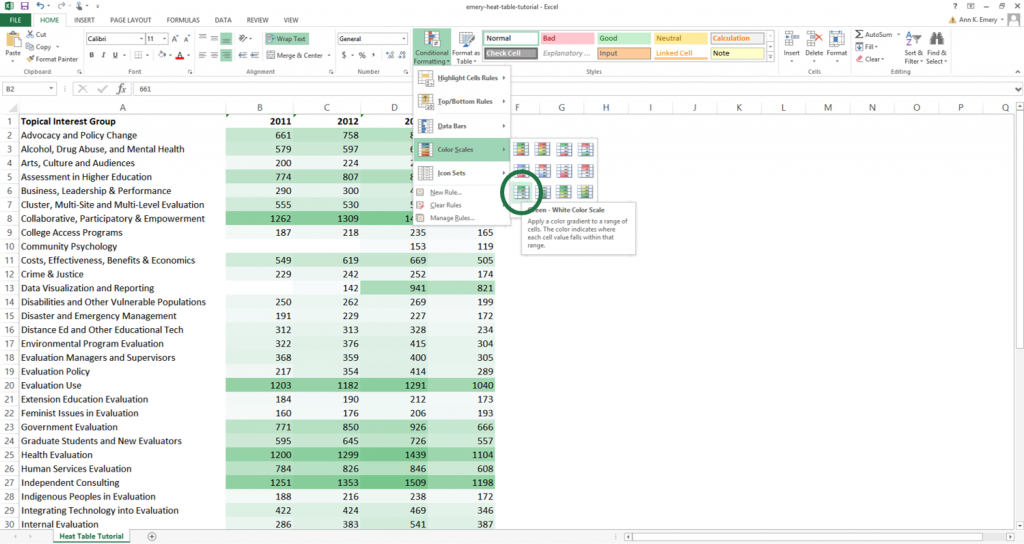

I also use exploratory computer strategies, like Microsoft Excel’s spark lines, data bars, and conditional formatting, to help me narrow down the focus of my charts.

Spark Lines

Here’s a tutorial that shows you how to get started with spark lines:

Data Bars

And here’s a tutorial that shows you how to get started with data bars:

Conditional Formatting

You can set up rules in your spreadsheet that automatically change the color of certain cells based on their values. I regularly use heat tables to scan my dataset for patterns. You can follow my step-by-step tutorial to make heat tables for your data.

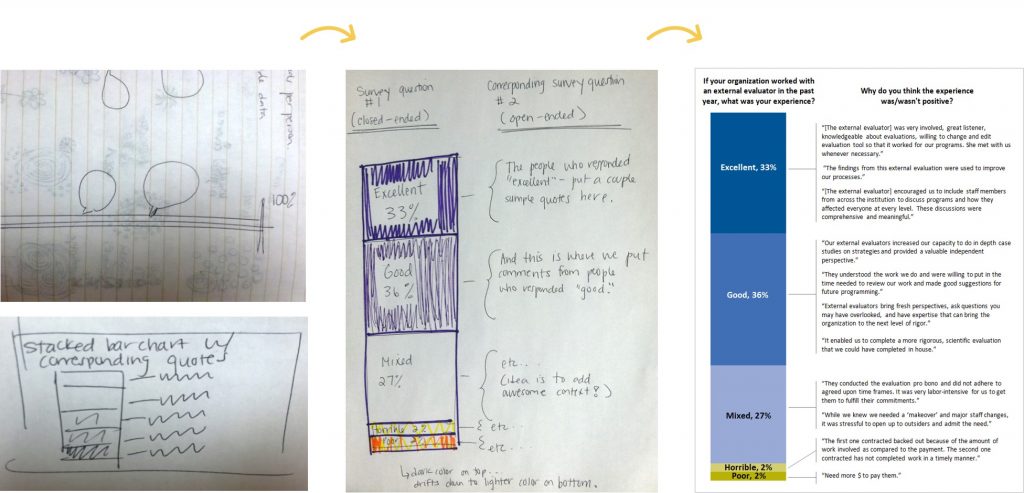

Sketch Rough Drafts on Paper

Step back from your software program. This is especially crucial if you’re using Excel or R (versus Tableau) where you usually need a solid idea of your chart’s design before implementing that design on the computer.

I sketch, draw, and doodle plenty of drafts before I create anything on the computer.

Here’s how it works: First, sketch plenty of rough drafts on paper. Give yourself permission to doodle as many drafts as you need. Share drafts with colleagues early and often. Gather as much feedback as you can. Next, create one or two of those promising drafts on the computer. Finally, edit, edit, edit! Put your easiest-to-follow chart in your final presentation or report. You might sketch five or more drafts. Only the single best chart will survive the editing process.

Step 3: Select a Software Program

Once you’ve got a rough mental idea of what your visualization might look like, sit down and build the first draft of your visualization on the computer.

There are dozens of software programs available for building data visualizations. Some are free. Others are low-cost. And others are quite costly, at least for smaller organizations.

Step 4: Declutter

After you’ve got the first draft of your data visualization created on the computer, it’s time to refine your visualization and make your message shine. No computer program is perfect. You’ll have to roll up your sleeves and make intentional edits no matter which software program you’re using. The very first edit I make is to declutter my visualization. Software programs come with way too many borders, lines, and unnecessary ink. Examine each and every speck of ink on the chart. Does it have a specific purpose? If you can’t articulate a reason for that ink, you don’t need it.

Apply the Squint Test

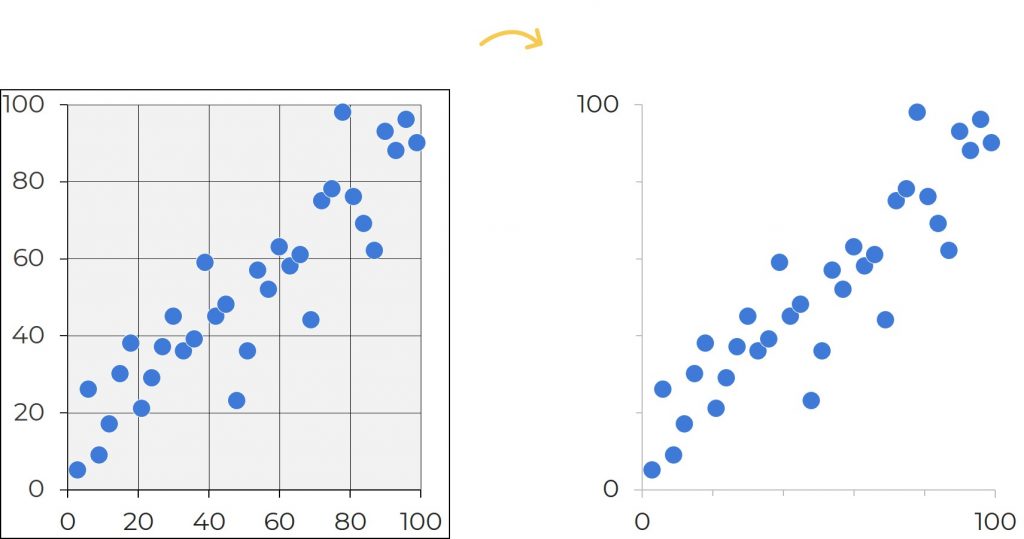

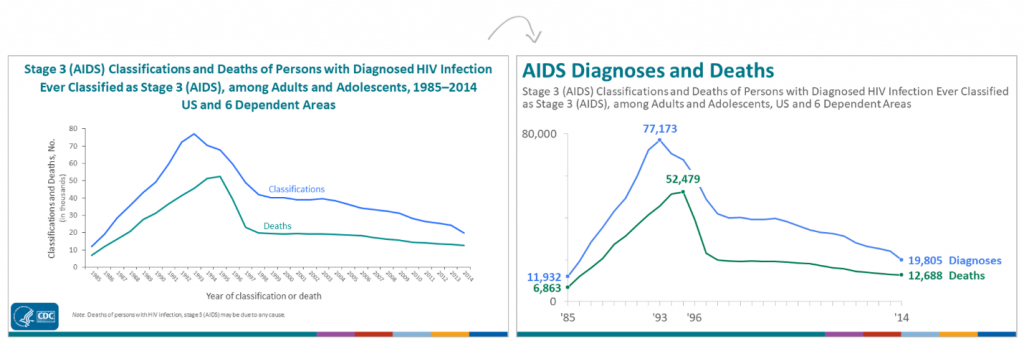

In these before scatter plot on the left, the cluttered appearance distracts us from the data. All these extra lines make the charts look overly scientific—and outdated. In the after version on the right, I removed the background shading and borders. I kept the x and y axes and some of the grid lines, but I intentionally changed the black ink to gray ink.

How do you know when you’re done decluttering? Apply the Squint Test. Here’s how it works: Squint your eyes so that you’re peering at the chart through your eyelashes. Everything should look a little blurry. Can you see the overall shape of the data? For example, you should be able to tell if a line chart is jutting upwards or downwards over time. If not, try removing more clutter.

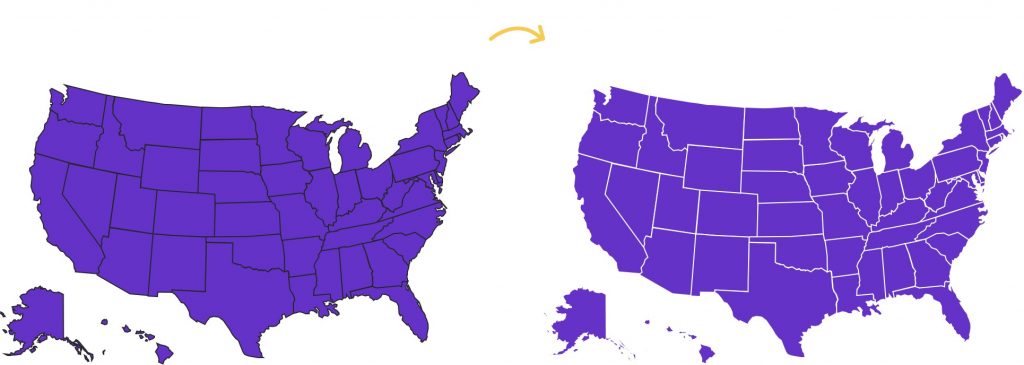

Outline Shapes in White

Sometimes reducing clutter means outlining shapes in white, rather than black, so that they match the chart’s background color.

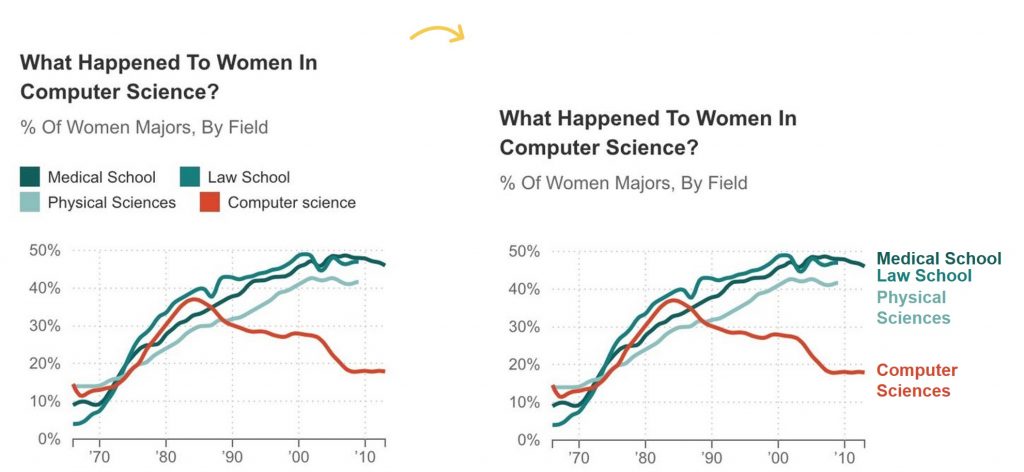

Delete Legends and Directly Label the Data

Although we’re used to seeing legends, we rarely need them. Legends can lead to unnecessary zig-zagging around the screen or page, and legends can also be difficult to interpret if your graph is printed in grayscale. Instead of using legends, directly label the data. Direct labels mean that you add labels as close as possible to the data. For example, in a line graph, you would delete the separate legend and place the category labels off to the right of each line. For bonus points, color-code the text in the labels to match the line.

Step 5: Clarify Your Message with Color

Colors are one of the most powerful elements of a chart, so choose wisely. There are a couple steps to choosing colors. First, select a color palette to match your client’s look and feel. Second, guide the reader’s eyes and attention with your action color.

Brand Your Visuals with Custom Colors

I’m begging you! Do not use the default colors from Excel, Tableau, or Google Charts. Nothing screams novice! or 2002! more than default color schemes. If you’re designing charts for a report, handout, or presentation for a client, use their color scheme. Consultants, this means the report will look like it came from the client. It will not have your firm’s look and feel.

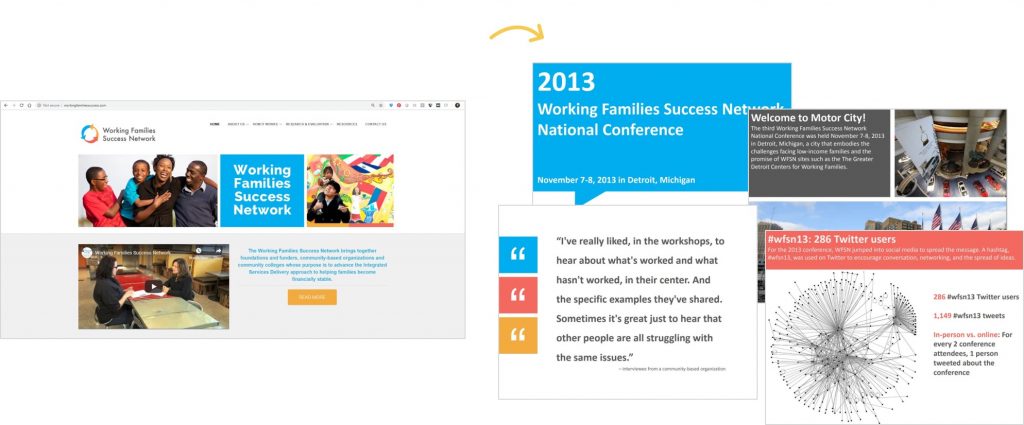

In this example, Johanna Morariu and I were designing a slidedoc for the Working Families Success Network. We began by investigating the Working Families Success Network’s logo, website, and publications. Their logo has a distinctive blue, orange, and pink and their publications use dark gray text rather than black. Throughout their website they use color blocks with white text and white outlines. Next, we adapted that layout and color scheme for our slidedoc. The images on the right are separate slides (pages) of the report.

You can locate custom color codes in style guides, with a free eyedropper tool, or even with Microsoft Paint. Then, enter your custom color codes in Microsoft Excel or in Tableau.

Make Sure Your Colors Are Legible in Grayscale

On-screen reading is getting more common, but chances are, someone will still be printing your visualization. Color printing is expensive, so your visualization will probably be printed in grayscale instead of in full color. I like to test my drafts ahead of time to make sure they’ll still be legible even if they’re printed in grayscale. You can test your drafts a couple of different ways. First, you could simply print one draft in full color and another draft in grayscale and then compare then side-by-side. Or, you could simply preview your image file in grayscale so that you don’t have to print anything at all. In Microsoft PowerPoint, for example, you simply click on your image file to select it, and then go to the Picture Tools: Format tab along the top of your screen. Then, go to the Color icon and Recolor your image file in grayscale.

Make Sure Your Colors Are Legible for People with Color Vision Deficiencies

Upload your draft to www.color-blindness.com’s Color Vision Deficiency Simulator.

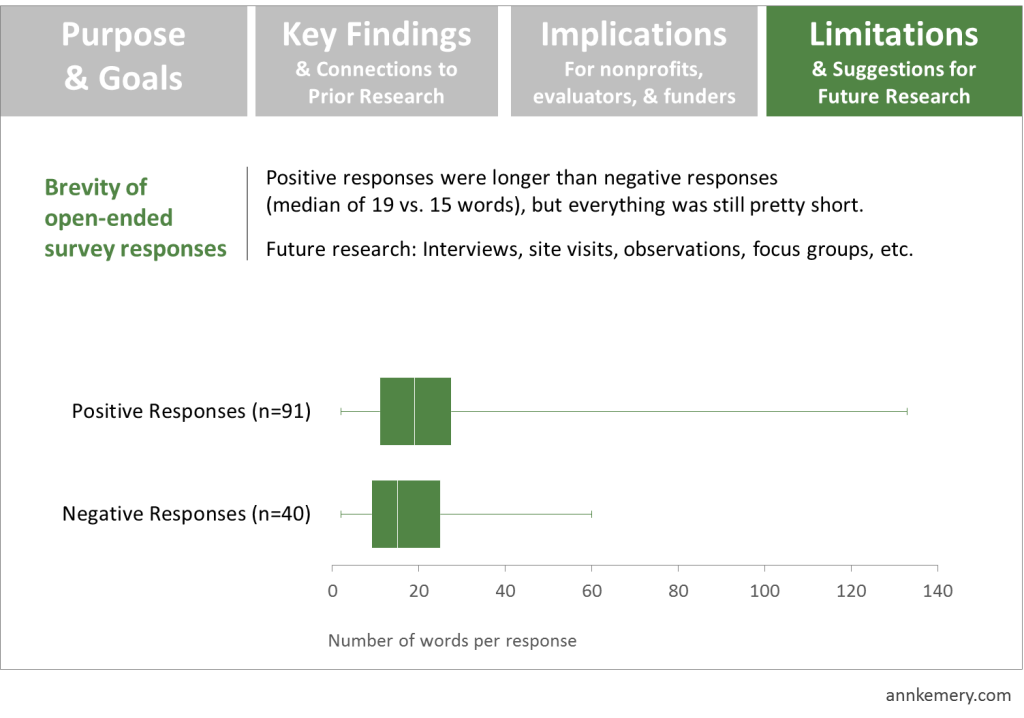

Emphasize the Takeaway Message with the Action Color

When you want to tell a story with data, you can guide your viewer’s attention to your desired takeaway finding by creating a dark/light contrast. This example comes from one of my graduate school projects a decade ago, so I used the exact shade of green from my university’s logo. Then, I used dark green to draw my audience’s attention to a couple key parts of the slide. This slide comes from the fourth section or chapter of the presentation, the Limitations section, so that tab was highlighted in dark green so that it contrasted with the other tabs, which are in gray. The topic of this particular slide was Brevity of open-ended survey responses, so that text is in green so that it stands out against the rest of the text. And the box-and-whisker plot itself also uses dark green.

Step 6: Clarify Your Message with Text

It’s hard to get wording just right, so I usually save my titles, subtitles, and annotations for the end.

Brand Visuals with Custom Fonts

Rather than using Microsoft’s plain ol’ Calibri, make sure your visualization’s fonts match the project’s branding.

Write the Takeaway Finding in the Graph’s Title

Need to tell a story with data? Rather than using a generic title (“Figure 1” or “Number of youth served”), state the takeaway message in the title.

I first learned about this technique through Cole Nussbaumer’s Storytelling with Data workshop back in 2012—but geez, was it tough to apply! This is one of the hardest practices for social scientists to learn because we’re so comfortable with APA formatting and its generic figure titles.

Think Twitter-like and aim for six- to eight-word titles. Look to newspaper articles for inspiration; journalists know how to include the “so what?” in their title. You may or may not read the full newspaper story for additional details. Same thing with charts: your audience may or may not read your full chart, so your title must give them the gist of your findings.

Annotate

Annotations are call-out boxes that provide important contextual details. In PowerPoint, Word, or Excel, you can easily create annotations by inserting a text box. No fancy software required!

Here’s a great example from Mother Jones. A generic title would’ve been “Number of children living in poverty” or “Relationship between poverty and geographic location.” This 6-word title, “In Climbing Income Ladder, Location Matters,” ensures that readers grasp the chart’s message instantly. A 2-line caption adds more details underneath the title, and a few cities are annotated. The tweet’s text also reinforces this message.

This is how likely poor kids are to grow up and move out of poverty based on where they live http://t.co/5A5VIZkLBN pic.twitter.com/7BBZQJ9bdg — Mother Jones (@MotherJones) January 31, 2014

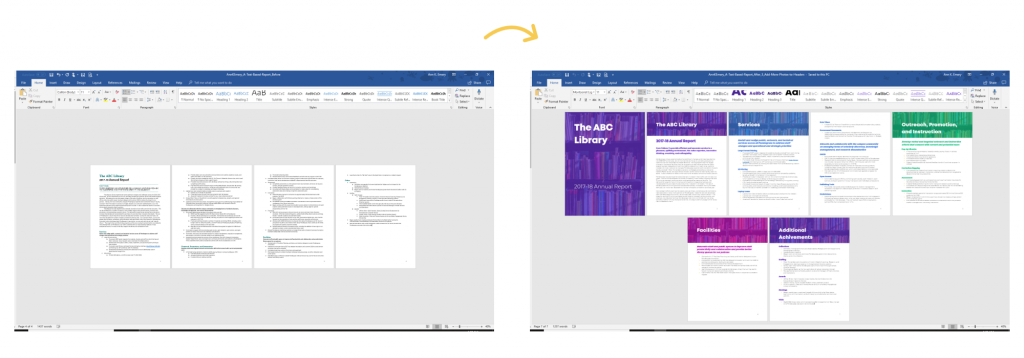

Establish a Text Hierarchy

Size your fonts according to their importance. A text hierarchy tells your viewers which information is most important (headings) and which information is least important (the regular ol’ paragraphs). In this example, I transformed a university’s annual report simply by adding an intentional text hierarchy. I call this makeover a two-hour turnaround because these are changes that anyone can make in two hours or less. Before, all the font was the same size, so the headings didn’t stand out. The report looked like a sea of words. After, we made the headings stand out by with larger fonts and by overlaying the text on top of a photograph. We also used a different color for each section to break up the sea of words into manageable chunks.

Lower the Reading Level

The vast majority of reports, handouts, infographics, dashboards, and slideshows that I review with clients are written at a reading grade level that’s so high that reading the documents feels like homework. In this example, we assessed our draft’s reading grade level with a free tool called readable.io. Then, we re-worded the title so that it was a closer match for our intended audience.

Step 7: Are You Doing It Right?! Test Your Draft

Woohoo! You’re almost finished. Check your progress with these self-assessments.

The Significant Other Test

aka the Grandmother Test. Give a draft of your chart to a significant other or coworker. Ask, “What’s the central message in this chart?” If they hesitate more than a few seconds, or if their story doesn’t align with your intended story, try working on your title and caption.

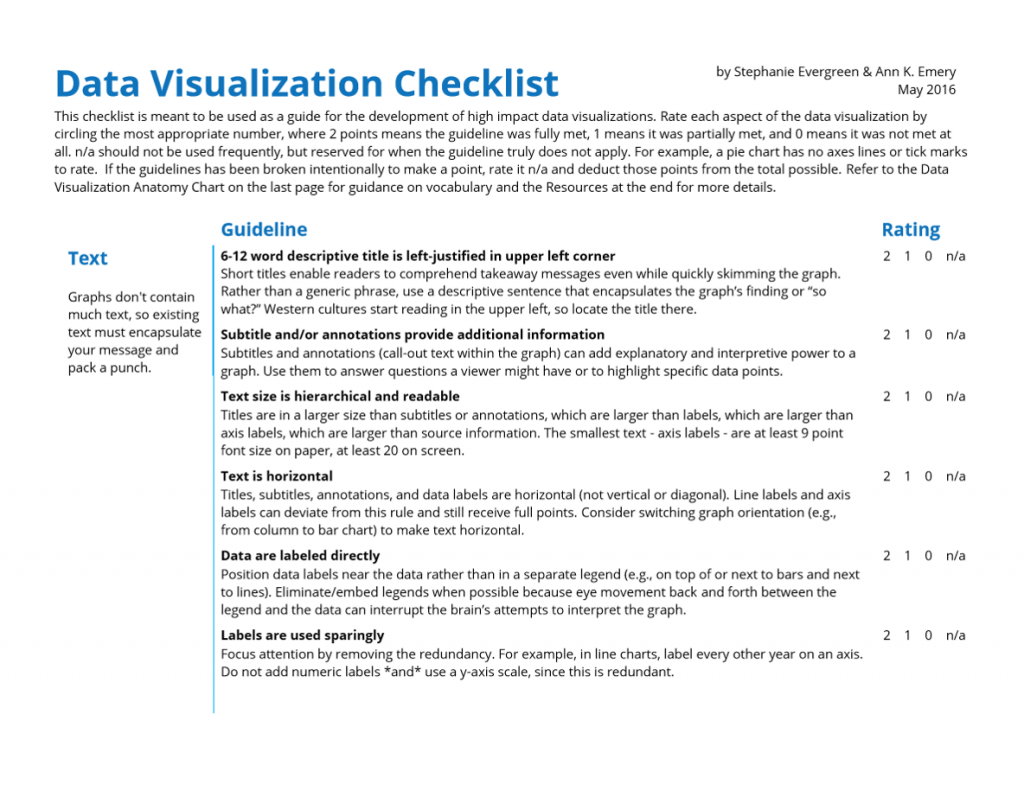

Use the Data Visualization Checklist

Stephanie Evergreen and I designed the Data Visualization Checklist in 2014 and updated it in 2016. You can use the checklist to help you assess your drafts.

Step 8: Share Your Completed Data Visualization

The final step in my Data Visualization Design Process is to adapt your visualization to fit different dissemination formats, like presentations, webinars, handouts, and social media.

Tips for Sharing Data Visualizations in Presentations

During conference presentations, presentations at staff meetings, or webinars, try breaking up your chart into several slides. Think storyboarding or animation. This takes a while to learn, but is well worth the learning curve.

Here’s a storyboarding example where I share key statistics about the American Evaluation Association’s Data Visualization and Reporting Topical Interest Group:

Tips for Sharing Data Visualizations in Webinars

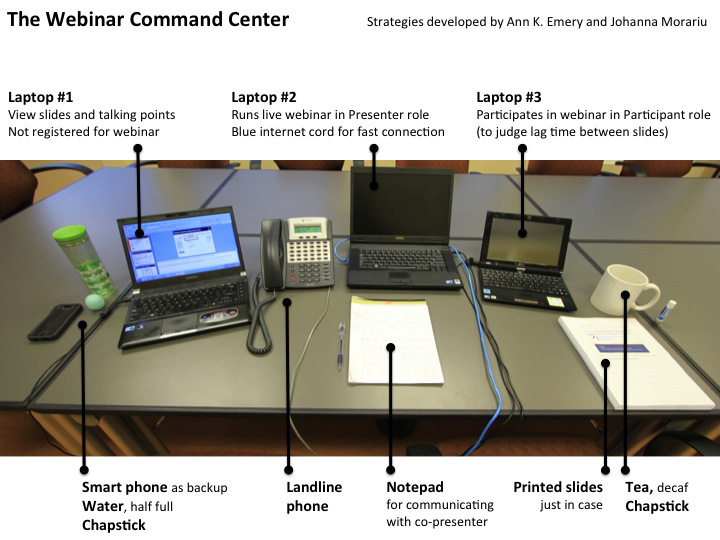

I regularly share results from research studies during webinars. Webinars are a unique setting and require a unique skill set. One of the things that makes webinars unique is that you’ll want to pay careful attention to your physical set-up. Here’s what my desk looks like when I give webinars:

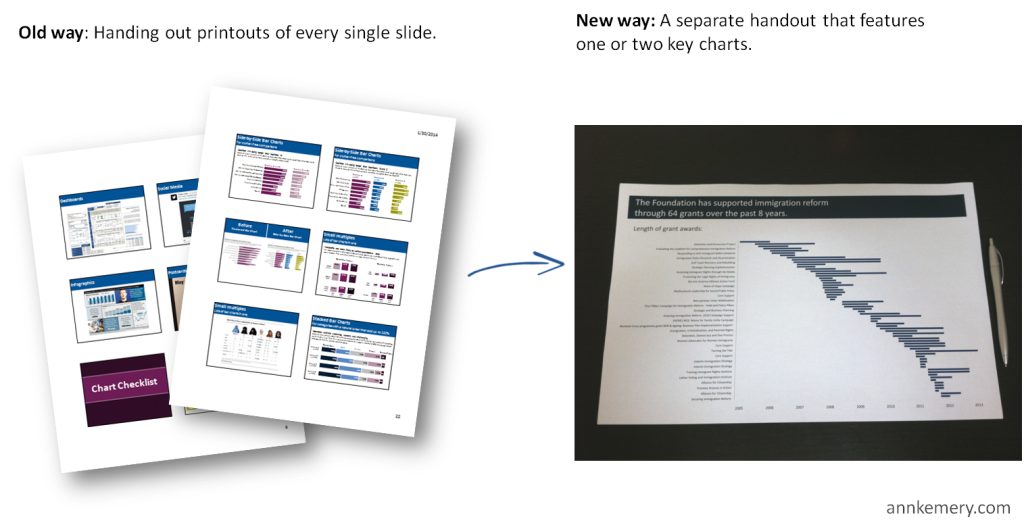

Tips for Sharing Data Visualizations in One-Page Handouts

We often print our full slideset for our audience. However, these “slideuments,” as Nancy Duarte calls them, are pretty much worthless. Our audience gets lost in pages and pages of details. One strategy is to produce a separate one-page handout with your most important chart. Now, the audience will walk away from your presentation with a crystal clear picture of the key message you wanted them to hear.

Tips for Sharing Data Visualizations on Social Media

Planning to tweet a chart or two? Twitter images have a 2:1 aspect ratio. This means that when you’re scrolling through your Twitter feed, the images automatically display about twice as wide as they are tall. Make sure you adjust your charts to fit a 2:1 aspect ratio; otherwise your carefully crafted title will get cut off. Check out the Ultimate Guide to Social Media Image Dimensions for more tips on sizing charts for each channel.

Another consideration is that a chart might be completely wrong for your Twitter followers altogether. An alternative is to overlap findings on photographs, which adds valuable context for the audience.

Do you text your spouse/partner when you’re both home but in different rooms? You’re not alone http://t.co/545hmnXcQT pic.twitter.com/sGp5XqdqyF

— Pew Research Internet (@pewinternet) February 11, 2014

Tips for Sharing Data Visualizations in Dashboards

Now that you can create a single chart, combine several charts to create a dashboard or infographic. Sometimes people use dashboard and infographic interchangeably, but these visual modes are quite different.

Dashboards are for internal audiences (for example, to help directors make decisions about a program’s future). Dashboards provide key metrics about a program, department, or organization, usually at regular intervals over time (e.g., quarterly reports to your Board of Directors).

Tips for Sharing Data Visualizations in Infographics

Infographics are for external audiences (for example, to increase awareness about your issue).

They’re usually designed for large masses of the general public—not just a handful of key decision makers, like dashboards—so they include plenty of explanatory text.

Charts are often grouped together so that you can “read” the story from top to bottom.

Learn More

Sign up for my free online course called Soar Beyond the Dusty Shelf Report. There are several quick lessons that help you get started with data storytelling.

Or, contact me about online courses, private workshops, and conference keynotes.