This is an Eval Central archive copy, find the original at rka-learnwithus.com.

By: Emlyn Koster

Emlyn recalls how Liberty Science Center, located across the lower Hudson from Manhattan and where he was President & CEO from 1996-2011, assisted the next-of-kin and surrounding community in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center on and after September 11, 2001.

Every year it seems, the museum world is jolted by breaking news of damage or destruction of an institution due to a fire, natural disaster, or an invasion. Recent examples are Brazil’s National Museum in Rio de Janeiro, Haiti’s Art Museum in Port-au-Prince, the Museum of Chinese in America in Manhattan, and antiquities in Afghanistan. Museum associations, including ICOM and the US Committee of the Blue Shield, may step in to help salvage collections. However, not making headline news―but the focus of this post—are situations of museums in the vicinity of a disaster which, while not directly impacted, assist next-of-kin and surrounding communities.

Twenty Years Ago

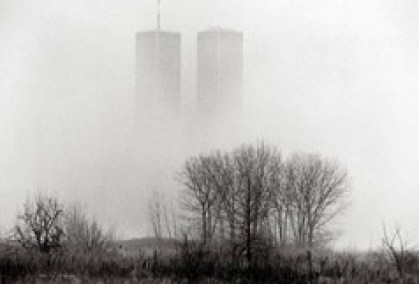

My vivid memory of the terrifying event across Liberty State Park and the lower Hudson from Liberty Science Center (‘the Center’) in full view of the World Trade Center’s twin towers has interwoven parts. Foremost is distress over what transpired at Ground Zero: the second is the aftermath involving the Center. Below is my recollection of an early moment that began the preface in a book about fostering empathy in museums:

“One afternoon in late September 2001, I joined a ferry taking several hundred next-of-kin of New Jersey victims from the World Trade Center across the Hudson River to Lower Manhattan’s North Cove Marina, the closest dock to Ground Zero. Grieving family members clutched teddy bears given to them as we boarded. Arranged by the New Jersey Family Assistance Center at Liberty State Park… this trip was their first opportunity to visit the remains of the fallen World Trade Center twin towers. Anxiously huddled together, we slowly walked past ash-laden trees and walls covered with frantic messages about missing loved ones, past emergency officials and site workers with bowed heads, across empty roads, and onto a makeshift platform overlooking the smoldering mountain of jagged debris. Weeping and whispering were the only sounds as we solemnly reflected on the riveting scene before us. Indivisible were the gravity and uncertainty of the entire Ground Zero situation and the overwhelming, deeply personal sadness of everyone there. Personal tension was exponentially compounded by the indescribable sorrow of the next-of-kin all around me” (Emlyn Koster, 2016. Foreword. In: Fostering Empathy in Museums, Elif Gokcigdem (Ed.), Rowman & Littlefield, vii-xi).

Below is a reprise of details in a requested article for a magazine one year after the tragedy (Emlyn Koster, 2002, A Tragedy Revisited, Muse, Canadian Museums Association, September/October, 26):

“Around 8:15 am on September 11, 2001, the car radio told me that my commute would be delayed by a major highway accident, so I detoured though local city streets. As the station interrupted normal programing to report that a plane had just collided with the World Trade Center’s north tower, the Manhattan skyline came into full view and I saw smoke billowing from its upper floors… I sped to the office and was met by several frantic staff... it had just become evident that the plane hitting the tower was terrorism, not an accident. I wasted no time in ordering a building evacuation… [we were] confronted with the biggest news story in recent memory and our faces and cries expressed our deepening shock and grief… We notified the region’s emergency authorities that our institution stood ready to help in whatever way it could. Soon, medical teams left with our first aid supplies, and commuters who had escaped the disaster site by ferry poured into our building. By late evening, several dozen mobile TV news units from across the eastern U.S. and Canada were set up around the same spot where the staff had gathered that morning.

… Liberty Science Center was closed to the public for two weeks. We continued to support the media, assisted with police communication needs, and were involved in a public vigil organized by the State. When New Jersey developed its plan for an assistance center for the families of victims, it was concluded that Liberty Science Center would be in a support mode to a full-service facility [at the Hudson River bank]… Working overnight with State government officials and aid workers, our staff helped to set up this Family Assistance Center. We processed all security credentials for its staff and volunteers, our caterer worked with the Red Cross to provide meals, and we had staff ready and trained for families of victims… We were also working with trauma counselors to help ourselves come to terms with what had happened and to guide us on how to interact with visitors when we reopened. We made changes to an exhibition about buildings and to advertising for our new giant screen film about the human body in sensitivity to the new issues on people’s minds. Over the following weeks, we hosted a wide variety of related events, including an international religious ceremony… Almost a year later, we continue to be a venue for follow-up events. We also participate in the Gift of New York Program which gives free museum visits to families of victims.

… September 11, 2002 will be a special day. The staff will gather for breakfast, as we did every morning during our closure last September, and we will share our memories. There will be a blood drive for staff and news crews will return to our site for live network feeds.

… I have thought a great deal about the broader learning for the museum field afforded by this experience. The lessons are many, particularly because September 11 occurred at time of increasing external consciousness on the part of museums.

… Does your museum have contact information for all emergency authorities in its region? Would you have to check with your board before closing and switching to an emergency assistance role? Do you have arrangements for assembly of staff elsewhere in the event of evacuation? Are computer records regularly stored offsite at more than one location? Can you access your phone system for changed public messages from the outside? Does your staff know how to access update information during an emergency or closure? What is your museum’s inventory of facilities and skills that could be useful in an area emergency and is this in the hands of those in charge of emergency planning? Have your museum’s learning environments ever served as a helping hand … at times of uncertainty and stress? … As the head of one of the mostly directly affected museums, I was proud of the way that Liberty Science Center did all it could to help. As an organization, we came closer together and we never blinked at the accumulating $700,000 direct cost of our participation... with a mission strongly rooted in social responsibility, we managed to approach an extreme situation with flexibility and fortitude.”

… Does your museum have contact information for all emergency authorities in its region? Would you have to check with your board before closing and switching to an emergency assistance role? Do you have arrangements for assembly of staff elsewhere in the event of evacuation? Are computer records regularly stored offsite at more than one location? Can you access your phone system for changed public messages from the outside? Does your staff know how to access update information during an emergency or closure? What is your museum’s inventory of facilities and skills that could be useful in an area emergency and is this in the hands of those in charge of emergency planning? Have your museum’s learning environments ever served as a helping hand … at times of uncertainty and stress? … As the head of one of the mostly directly affected museums, I was proud of the way that Liberty Science Center did all it could to help. As an organization, we came closer together and we never blinked at the accumulating $700,000 direct cost of our participation... with a mission strongly rooted in social responsibility, we managed to approach an extreme situation with flexibility and fortitude.”

Trauma psychologists promptly documented their reflections about the Center as a place for comfort in a time of need and about its partnership with The Families of September 11 which nurtured a curriculum for how schools could boost their resilience in troubled times (Donna Gaffney and Emlyn Koster, 2016. Learning from the challenges of our time: The Families of September 11 and Liberty Science Center. In: Fostering Empathy in Museums, Elif Gokcigdem (Ed.), Rowman & Littlefield, 239-263). I later surmised that the Center’s track record of commitment to the welfare of its community helped to propel it through this extraordinary period.

As Liberty Science Center reopened, a public service announcement in The New York Times, The Star-Ledger and Jersey Journal at no charge to the Center. This began: “The trustees, president, employees, and volunteers of Liberty Science Center express their heartfelt sympathy to the many families, friends and communities of those who suffered losses, were injured, or are still missing as a result of the terrorist attacks at the World Trade Center, The Pentagon and in Pennsylvania”. And it ended: “Liberty Science Center joins the countless other voices that call upon all of us to strive for greater global harmony… We also express our desire for the peaceful use of science and technology to create a better world”.

Wider Reflections

Thinking back, there were additional uplifting, and even some truly transformative, moments. These included a requiem in Liberty State Park featuring Andrea Bocelli, an out-of-the-blue six-figure donation from a pharmaceutical company who knew the Center was hurting financially, and the board’s adherence to a long planned first meeting of a facilities task force which would lead to an $109 million expansion and complete renewal of the Center.

“A spring 2002 survey showed that the staff foresaw significant advantages and opportunities in the Center’s expansion plans. These included renewed visibility, enhanced image, recharged spirit, a better working environment, new jobs for the community, and more and better offerings. But not surprisingly, the study also revealed questions about job loss, whether the organization had the capability to handle such a major project, and whether departments could work together well enough to deliver on the plans… Frequent communications about developments and reminder continued apace. Piece by piece, our planning became a reality… All in all, this has been a story of mission above self. The idea that Liberty Science Center could be a more useful resource to the diverse communities in its surrounding region always seemed to trump the anxiety of the moment” (Emlyn Koster, 2007, The Reinvented Liberty Science Center, LF Examiner, 10:7, 1-9).

Also in 2007, museum critic Edward Rothstein for The New York Times wrote: “The Center, which reopened yesterday after two years of construction, has been rethought and reshaped, with the goal of doing nothing less than reinventing the science museum”. He quoted me: “The science museum … should provide ‘resources for living, learning, working in and caring for its surrounding area’ … It should aim for ‘relevancy’ and have the ultimate goal of leading its visitor to a form of activism”. Today, my outlook is exactly the same. A few days before Rothstein’s review, The New York Times expressed this editorial opinion: “…The new center also tries to make science feel accessible, even local… To its credit, the center does not shy away from the things we wish were less real-world. The skyscraper exhibition holds two pieces of the World Trade Center; one is an I-beam mangled by the heat and pressure into a twisted U”.

As the world warms and violence increases, and with more of humanity living next to natural hazards, it is probable that museums will increasingly find themselves in helping-hand situations. I hope the foregoing reflection ago encourages institutions to be maximally useful if and when a disaster strikes nearby and thereby to boost their resilience.

About the Author

Emlyn Koster, PhD is a geologist who also became a museologist and a humanist. The CEO of four major nature and science museums in Alberta and Ontario, Canada and then in New Jersey and North Carolina, he is an advocate for the museum sector’s alignment with ‘glocal’ societal and environmental needs. Following September 11, 2001, community recognition included an award from New Jersey’s Arab-American Anti-Discrimination Committee and the Humanitarian of the Year award from the American Conference on Diversity. He is a member of the Ambassadors Circle of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience and involved in a new UNESCO-supported project about the global language of the Anthropocene. He welcomes comments and inquiries at [email protected]. You can read his previous blog posts for RK&A here.

The post When Disaster Strikes: Assistance by Museums Nearby appeared first on RK&A.