This is an Eval Central archive copy, find the original at freshspectrum.com.

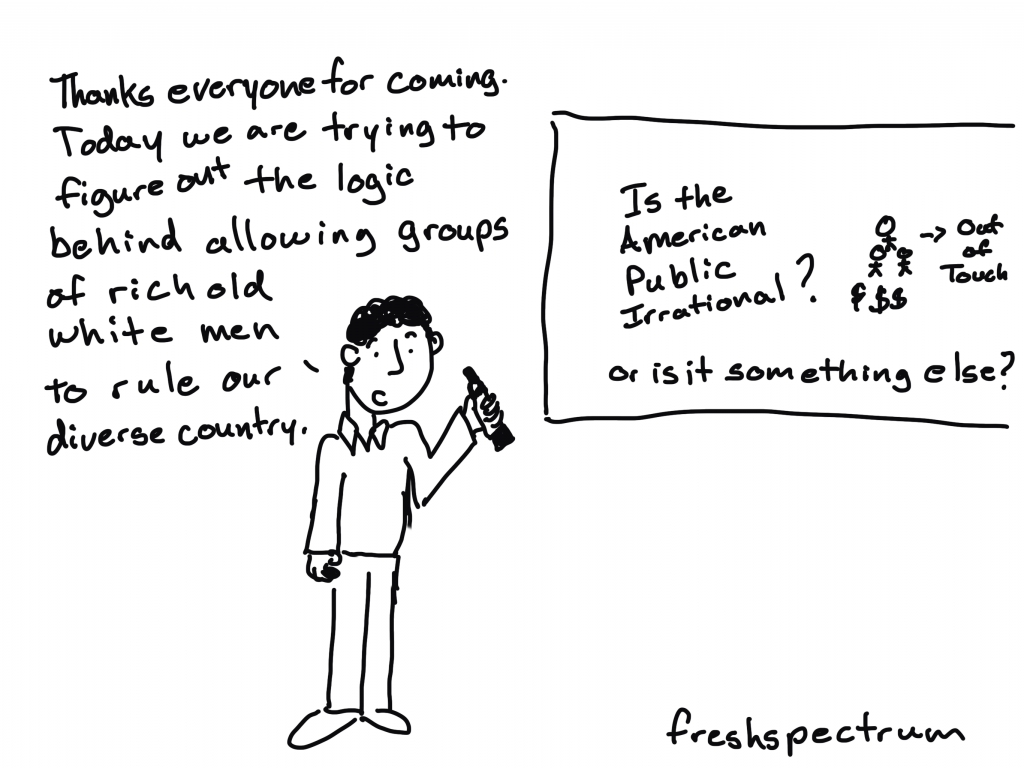

Evaluation as a profession is built around the rational. So what about the things that seemingly defy logic?

So this is sort of a cartoon illustrated philosophical brain dump week. I’ve been diving deep into my public library’s audio book collection and thinking a lot about rationality. If you don’t want to think, just skim through the cartoons. You’ve been warned.

I remember thinking a bit about evaluation when perusing some of Daniel Kahneman’s work on behavioral economics. Economics traditionally was based on this idea that people make rational decisions. Behavioral economics calls that into question and it led to a Nobel prize for the psychologist, Kahneman.

And Kahneman’s work can now be seen transcending fields. I mean it came up most recently when I was reading a book by hostage negotiator Chris Voss.

Everything we’ve previously been taught about negotiation is wrong: you are not rational; there is no such thing as ‘fair’; compromise is the worst thing you can do; the real art of negotiation lies in mastering the intricacies of No, not Yes.

I had been waiting for the idea to creep into the evaluation world. Like for someone to write a book titled behavioral evaluation. To start making claims that people are not rational so how do we expect to create accurate rational models of the activities of people?

His central message could not be more important, namely, that human reason left to its own devices is apt to engage in a number of fallacies and systematic errors, so if we want to make better decisions in our personal lives and as a society, we ought to be aware of these biases and seek workarounds.

Daniel Kahneman changed the way we think about thinking. But what do other thinkers think of him?

But lately I’ve been feeling like saying we are not rational is just a cop-out.

Of course we’re rational. We make rational decisions all the time. But my rational isn’t necessarily your rational.

My desired outcomes might be different, and who is to say my desired outcomes will even stay fixed. Have you ever lost a game on purpose? Taking it easy on someone to help build their confidence. Or maybe another player does something that annoys you. Does changing your desired outcome from “winning” to “making sure that one jerk loses” mean you are not rational?

Maybe, just maybe, it’s not a lack of logic we’re noticing. It’s just people who don’t do what we think they are going to do.

It’s not the work of white Nobel prize winners that we need to see further integrated into our field. Perhaps though, it should be the work of feminist thinkers like Audre Lorde.

Rationality is not unnecessary. It serves the chaos of knowledge. It serves feeling. It serves to get from this place to that place. But if you don’t honor those places, then the road is meaningless. Too often, that’s what happens with the worship of rationality and that circular, academic, analytic thinking. But ultimately, I don’t see feel/think as a dichotomy. I see them as a choice of ways and combinations.

But of course it has already.

I find myself “discovering” works well known to many. Works that have already inspired countless, and will only continue adding to those numbers over time.

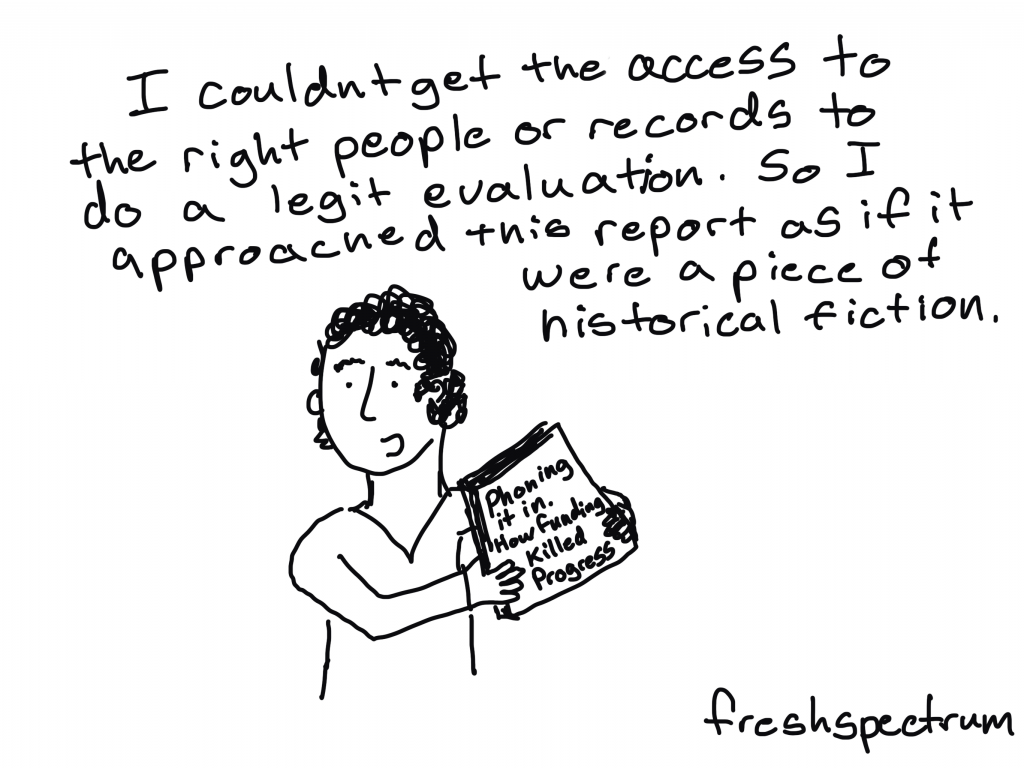

I soon recognized that there was a severe disconnect between the grantmaker’s success measures and the mission and/or approach to the work of many of the grantees. I wrestled with how to provide enough insight toward demonstrating some sense of accountability for the grantmakers while also creating space to use the evaluation findings to support grantee effectiveness (e.g., delivering technical assistance).

I discovered along the way that the root of this disconnect was not a grantee’s ability to be “successful”, but the varied definitions used for success. While struggling to figure out how to effectively address this observation, I recalled the words of Audre Lorde, an author whose writings I fondly admire and reflect on regularly. In other words, many grantees are trying to “crunch” their work into someone else’s definition of success, and in that process, their true efforts and impact go unnoticed.

The Day Audre Lorde Inspired Me to Reconsider the Definition of Success by Alison T. McMcNeil

So wait, where was I?

Oh yes, rationality.

I think this is the lesson that’s now stuck to my heart.

Desired outcomes are as infinite as our motivations. In a single person they can change quickly with new context, or gradually over time. In groups of people they are never fixed.

As evaluators, we need to seek out these motivations and desired outcomes, both written and unwritten. Because rational exists, and that rationality is essential to understanding how programs work or do not work.

It just might not be the rational represented by the official program theory of change.

We believe the one who has power. He is the one who gets to write the story. So when you study history you must ask yourself, Whose story am I missing? Whose voice was suppressed so that this voice could come forth? Once you have figured that out, you must find that story too. From there you get a clearer, yet still imperfect, picture.