This is an Eval Central archive copy, find the original at medium.com/innovationnetwork.

“The truth is, structure matters. How you do your work is equally as important as the work itself”

Kendra Hicks — Resist Foundation

Author’s note: I started working on this blog post in May 2023, only a few weeks after we began piloting the decision-making structures and processes whose co-creation is described below. Then, we had not yet implemented these systems so the post doesn’t describe how they are working out in practice, which is something we are reflecting on in an ongoing way and will share in the future. Still, we wanted to be open about what has emerged for us so far, as a way to learn together and be in community with others who are transforming their organizational governance in similar ways.

Our journey itself has been inspired by Emergence Collective, a Michigan-based learning and evaluation firm that has co-created and operated according to a co-op model since its inception. We are deeply grateful to Lauren Beriont who generously shared information and materials about their governance structure and the process they used to create it, which we have perused and — where appropriate — modeled our journey and the structures we created on. As I wrote this blog, Lauren also kindly offered to write an addendum for it. I am delighted that you will hear her voice as well as mine, as Emergence Collective has been an incredible source of inspiration throughout our journey.

When I joined Innovation Network just a little over three years ago, the last thing I expected was that I would have found myself leading the organization after two years. When Alissa Marchant and I became interim co-directors in April last year, there was very little we knew about what it takes to steward an organization — particularly one that was healing from trauma and is on a journey to center equity and social justice. There was one thing that we knew for sure: we did not want to nor could do it alone. While our titles were fancy, we were aware that we did not know more than the rest of our team so, instead of pretending that we did and using that as a flimsy excuse to justify the positional power we found ourselves holding, we decided to try a different type of leadership, one that valued and harnessed the experiences and knowledge of every single member of the team.

To transform the whole organization, we thought the entire team should lead in the decisions that mattered the most to them. We shared this vision with the rest of our colleagues, and by common accord, collectively embarked on a process to transform our decision-making to more horizontal, team-led structures that share power across the different positions and roles and center junior team members and team members from communities that have historically had less power and privilege.

Co-creation process

Our collective process had the ultimate goal of creating a decision-making framework that articulated how and by whom decisions would be made so that our decision-making would embody our values while allowing us to move along at the pace required by our work which — as an organization that provides consulting services — can be hectic at times. To achieve this, we met for 12, 1.5-hour sessions over eight months. The entire team, as configured at the time and inclusive of interns, participated in every session. I created and facilitated the process. In an ideal world, we would have hired an external facilitator or, short of that, the process would have been co-led with a team member with less positional power. Neither solution was feasible at the time. To mitigate this, we did a few things:

- Used a consent-based decision-making approach (i.e., every person involved can live with the decision made) throughout the process. The team consented to my facilitation as well as to the overall process trajectory and the individual sessions’ objectives.

- Set norms for the co-creation space. To create what a team member called a “brave space” (as it would be disingenuous to call it a safe space, given the power differentials). At the start of the process, we collectively set norms to support the full participation of all team members involved, acknowledge and help mitigate power dynamics, and constructively handle disagreements if they arose. Norms were revisited throughout the process to see if edits or additions were needed.

Decision-making framework

How will decisions be made?

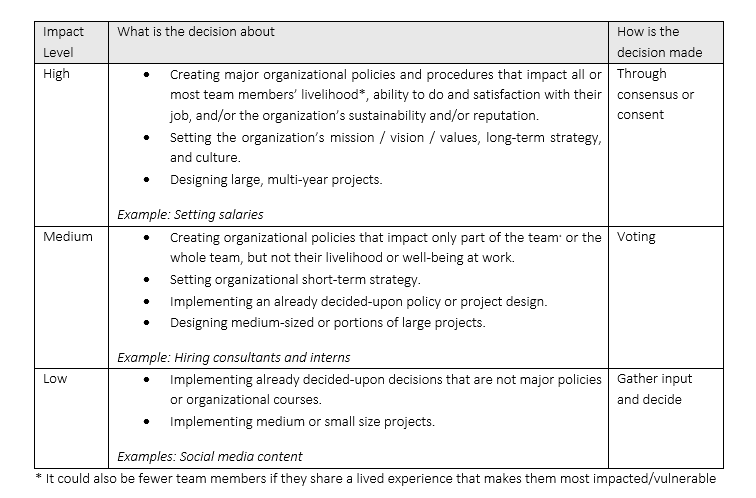

Through our process, we examined the most significant and/or common decisions that we make in our work life and collectively decided what decision-making approach we would use for each. We considered both organizational decisions such as creating new policies, as well as decisions related to our client-facing work. In doing so, we noticed a close correlation between the impact of and the desired approach for the decision: the more impactful a decision, the more participatory the approach we decided to use (see framework below). While we were concerned that using consensus or consent approaches would make decision-making cumbersome and slow, we are quickly realizing that being a small team of people who have built trust and care for each other makes unanimity-based processes much speedier than their reputation. Also, using a sociocratic consent process provided us with a clear roadmap to undertake complex decisions.

Who participates in decision-making?

For medium- and high-impact decisions, all people who are impacted by the decision get to be involved in it, if they want to. This is the cornerstone of how we want our decision-making to be aligned with our values, particularly that of furthering equity. Actualizing it runs up against two opposite tensions:

- Determining who is or is not impacted can be tricky. We decided that people — including external consultants and interns — will be able to self-identify as impacted. If there are misaligning impressions among people involved on who is “impacted,” the rest of the team will have to consent to the self-identification.

- Balancing intent and capacity for participation is not always possible. While centering junior team members and team members from communities that have historically had less power and privilege sounds great in theory, we also wanted to make sure that we were not “putting the labor of equity” on them. If the people closest to the decision don’t have the bandwidth to be involved as much as they would want, other team members — particularly those with more positional power — will step in to do the legwork, ensuring that most impacted people/people with lived experiences are appropriately involved, within the boundaries of their capacity and interests.

Growing edges

This may sound like a complicated dance, and we anticipate it will be, at times. Transforming decisional structures is not easy, particularly for an organization embedded in an ecosystem of relationships with actors who also hold significant power like our board and our clients and partners. Cognizant that this is an experiment, we also agreed to put safeguards in place to make sure that we stay true to our vision for decision-making while navigating the tensions that doing so may entail.

Mitigating positional power and other forms of oppression

While we are trying to shift power, we are still operating — at least for now — within the constraints of a traditional nonprofit organization structure in which the Director — who answers to the Board — has the ultimate responsibility for the organization. We also still have other staff levels (Associates, Senior Associates, etc.). We are starting to discuss how our structures may need to change to better align with our values. Our recent decision to nominate Alissa Marchant as Innovation Network’s Director was made collectively by the team and board through a consent-based process led by an external facilitator.

Still, we cannot equate transparency with equal power in decision-making. Anyone who has concerns that abuse of power or other forms of oppression are going on will be able to veto a decision. Vetoing will move the decision to a higher decision-making category. We also agreed to create a whistleblower process. Feedback shared through this process will be available to all team members and the board. Finally, we acknowledge the need to collectively decide what accountability will look like at Innovation Network.

Having clear fallback processes

We know that timelines, capacity, and other external constraints misaligned with our values, as well as potential unresolvable disagreements among team members will stand in the way of conducting decision-making as we have agreed upon. We laid out a few strategies for mediating between the pressures of a consulting organization and living into our vision for decision-making. For example, we agreed that at times we may need to make “placeholder” decisions and set plans for iterating such decisions when the necessary conditions are in place to make them according to our agreed-upon structures and processes. At the same time, we understand that a lot of the sense of urgency we experience is rooted in white supremacy and commit to creating and advocating for the necessary conditions to conduct decision-making as we have agreed upon. We have set funds aside to hire external facilitators and mediators if we need support for crucial decisions.

Creating both ongoing and set opportunities for iteration and learning

Ultimately, we accept that this is an experiment and know that all pilots require ongoing learning as well as the possibility to fail. At this point, we are reviewing our decision-making every time we make a decision — even if it is just a gut check that we are acting according to our vision for a horizontal, team-led approach. We will also be setting times — hopefully in person — to conduct formal, overarching reviews. Finally, we were excited to share our decision-making structures and processes with our newer team members, asking them to use their fresh perspectives to identify opportunities to strengthen this model.

Reflections and next steps

In truth, our journey was much more than co-creating the decision-making framework. Making the time and space to envision and articulate how we wanted to decide about our life at work also drew us closer together at this transitional time by helping us understand each other more, what our values and priorities are, and how we can be kind as well as truthful when having hard conversations. Possibly, the most important outcome of this process has been building true connections among us and the belief that when entrusted with decisions, each of us will make them keeping everybody’s best interest at heart.

We are curious and optimistic about how this all will shake out. Expanding our team, doing strategic planning, and figuring out what growth can look like for all of us in a relatively small organization will all be interesting opportunities to pressure test our new decision-making. We will keep you in the loop and would love to hear from you: both if you want to poke holes in our thinking and if you are also considering and working to change your organization’s governance to be more democratic. What are you learning? What are some of your growing edges?

From Lauren Beriont at Emergence Collective

I’ve found in my work on justice and equity a tendency to conflate trust and implicitness. For me there is a voice in my head that says “We should just trust each other” or “I don’t want to be too process-heavy” or “I don’t want to leave an impression that I don’t trust my colleague’s experiences or ways of working”. I’ve learned however that being explicit is a way to build trust that is just and equitable and that our default towards implicit processes is really about our own assumptions and discomfort.

At Emergence Collective (EC), even though it has been over 5 years, it still feels like we’re at the beginning of a grand experiment. In many ways we are — just in the past six months, we ourselves revisited what shared decision-making looks like — our ideals and our realities — and how our co-ownership structure allows for or limits participatory decision-making on our team. I’ve left our internal discussions feeling strongly about how to keep these discussions alive, living, and not just an intellectual exercise that we did at a team retreat three years ago.

I’m so excited and grateful to Virginia for getting these ideas out there and continuing the conversation about explicit decision-making models. We at EC are certainly not perfect and have a lot to learn from continuing to unlearn and question motivations for how and why decisions are made internally and with our partners or clients.

Transforming our decision-making was originally published in InnovationNetwork on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.