This is an Eval Central archive copy, find the original at rka-learnwithus.com.

Since the reality of coronavirus set in back in March, our RK&A team has been having a lot of conversations about study design. Museum closures and social distancing have greatly impacted the way we do our work as evaluators. They have affected our clients, project timelines, data collection methods, and access to study respondents in one of our most frequent settings—the museum floor. Sampling has always been one of the top questions we are asked about, and it is something we very carefully consider when designing our studies, no matter if the study is small or large (see, for example, our previous posts on sampling transparency and sample sizes for qualitative and quantitative studies). One question I have been wrestling with lately in light of coronavirus is the idea of capturing a “representative sample”—that is, a sample that shares the same characteristics of the museum’s visiting population (or whatever population we are seeking for a particular study).

Often, when we recruit visitors for a study at a museum, we use a random sampling approach. The data collector imagines an invisible line on the floor, intercepts the first visitor to cross over that line, and asks them to participate in the study. After completing the interview or questionnaire with the visitor, the data collector returns to their recruitment location and selects the very next person to cross their imaginary line. The rationale for random sampling is that it is more likely to result in a sample that mirrors the museum’s visiting population (for more on sampling protocols, see Amanda’s post here). We use additional measures like comparing observable characteristics (i.e., estimated age and group composition) of visitors who decline to participate (our refusal sample) in the study with the sample characteristics to understand potential gaps in our sample. All of this information can be placed within the context of a museum’s known visitor demographics (from audience research or other sources) to understand whether a study sample is representative of the museum’s visiting population.

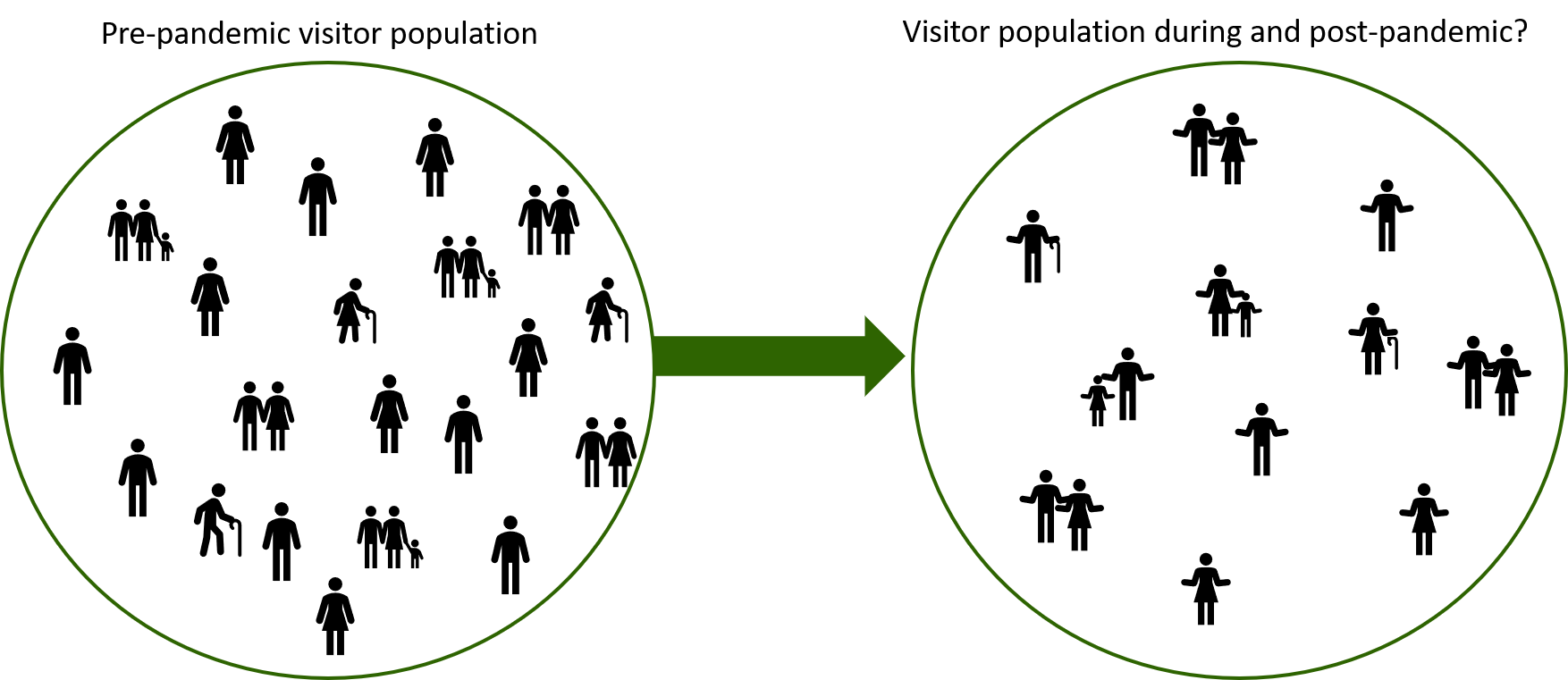

Under pre-pandemic circumstances, this is all well and good. But now, with the uncertainty of what visitation will look like over the coming months and potentially years as museums phase into reopening with limitations on visitor capacity and new social distancing measures, I wonder what does a “representative sample” mean now? Are we aiming for our study samples to be representative of the visitor population before the coronavirus? I’m not sure how useful that is considering visitation will probably not return to what it was pre-pandemic, at least not for quite a while. In addition to reduced numbers, it would not be surprising to see demographic shifts in visitation in response to the pandemic (e.g., fewer vulnerable groups, like adults over 60).

We always strive for rigor in our evaluations, and responsiveness and transparency in study design are equally important as we learn to adapt to our ever-changing world. As Heather Krause of Towards Data Science wrote in a recent blog post, “The goal is to retain as much value in the data you currently have and analyze and understand it in ways that make sense now.” I don’t yet have an answer for what a “representative sample” will mean for our upcoming studies, and I think the answer may vary based on the museum, exhibition, or program. Still, I can be responsive to both the circumstances of the pandemic and the needs of our clients by having frank conversations about sampling and what information will be most meaningful and actionable. And, I can make decisions and approaches clear in our evaluation plan and reporting so that we are all on the same page about what the data does and does not represent. I look forward to working toward a clearer understanding of what “representative” means for sampling in the coming months.

The post Sampling: What does “representative” mean during and after coronavirus? appeared first on RK&A.