This is an Eval Central archive copy, find the original at cense.ca.

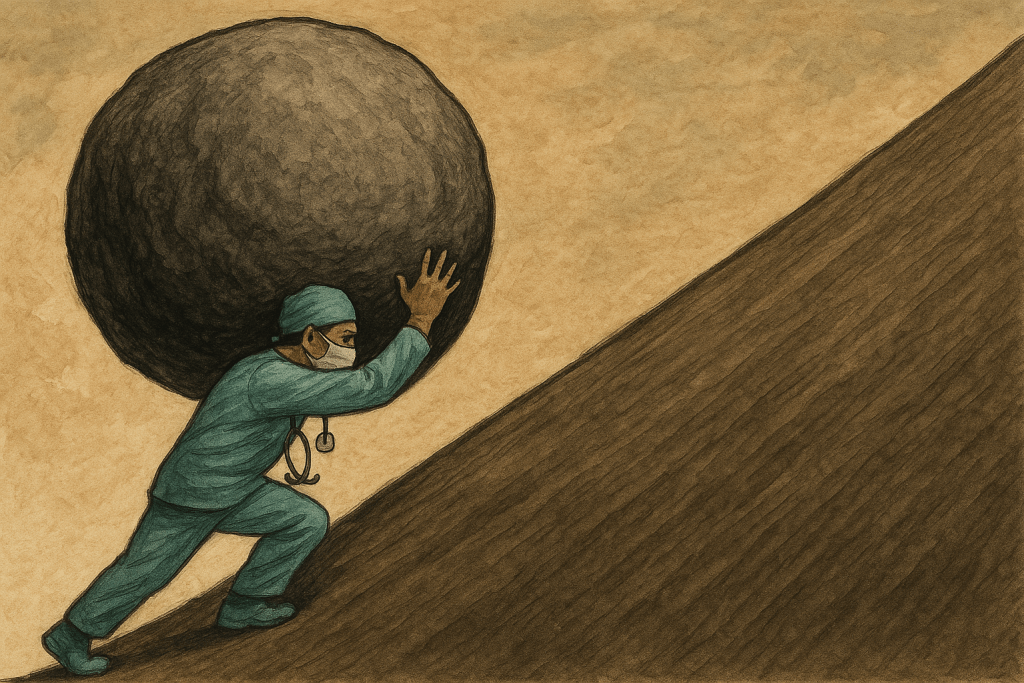

Maintaining focus and motivation within many health and human service-sector roles can be difficult. Clients continue to show up with issues that demand care and attention often without the means for practitioners to follow-up afterwards. It can be demoralizing. It can also be a source of frustration and low performance (as well as a means of encouraging people to leave the field).

In an article on Censemaking, we outlined the progress principle and how monitoring and evaluation data can contribute to staff motivation and performance, particularly in settings like healthcare where many professionals are simply in a ‘reaction and transaction‘ mode of service. They’re just trying to get things done, but often don’t see progress toward a bigger goal, which is what is among the top motivators and sources of job satisfaction for workers of all types.

In this first article, we look at monitoring and evaluation systems as a means of enhancing motivation, strategy and supporting both staff and organizations in making progress on bigger goals. We will elaborate on these in future articles.

Designing Data Systems for Progress

Capturing progress is important for individuals and groups for many reasons. Creating evaluation and monitoring systems that support this comes down to a few short, simple, non-technical things:

- Identify what moves people

- Emphasize light touch and nimble over sophisticated and inflexible

- Create a pathway and process to connect data collection, sensemaking, and use

- Evaluate (and repeat)

The technical aspects of this—the measurements and tools, data systems, and analytical plans—are secondary considerations (for the purposes here). If you don’t get these first four things right, you’ll just be designing technical monitoring systems. There’s nothing different that will come from it.

A monitoring and evaluation system is an interconnected set of actions, activities, and relationships. In this case, it’s connecting the reasons why people engage in health systems work with a mechanism to learn from the activities in that work. The system is then designed to illuminate pathways and processes to link the work, the activities performed, the outputs and outcomes associated with that, and indicate where the impact is.

The main purpose is to align what you do with where you’re going and what impact you have, using data from your practice.

Innovation and Learning Systems

The last part of this is to evaluate the work that you’re doing. It may take time to determine the specific qualities of the work, the role(s) that people play, and the particular jobs to be done (what people do in service of their roles). The specific aspects of this will be highlighted in the next article in the series.

This is part of an innovation and learning system. It doesn’t have to be fancy, it just needs to allow you as a leader to answer the questions: 1) what is going on? 2) what influence are my staff having on health problems and patient/client care? 3) how do I know? and 4) how can I tell this story to others?

Lastly, it’s asking how I can take this and use it to improve, maintain, or transform what we do?

That’s what an innovation and learning system is. If you set this up, you’re set.

(We’ll look at that in the coming articles in this series). In the meantime, reach out if you want to chat about how we can help you build this within your practice.

References (For Further Reading)

- Amabile, T. M., & Kramer, S. J. (2011). The progress principle: Using small wins to ignite joy, engagement, and creativity at work. Harvard Business Review Press. https://hbr.org/product/the-progress-principle-using-small-wins-to-ignite-joy-engagement-and-creativity-at-work/13361-HBK-ENG

- Amabile, T. M., & Kramer, S. J. (2011). The power of small wins. Harvard Business Review, 89(5), 70-80. https://hbr.org/2011/05/the-power-of-small-wins

- George, G., & Rhodes, B. (2018). Why do people become health workers? Analysis from life histories in four post-conflict and post-crisis contexts. Global Health, 14, 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-018-0414-1PubMed Central

- Maharaj, S. (2017). What Motivated Students to Choose a Career in Health Sciences? A Mixed Methods Study at the University of the Free State, South Africa. The Open Public Health Journal, 11(1), 44-53. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874944501811010044The Open Public Health Journal

- Tamayose, T. S., Madjidi, F., Schmieder-Ramirez, J., & Rice, G. T. (2004). Important Factors When Choosing a Career in Public Health. Californian Journal of Health Promotion, 2(1), 65-73.ResearchGate

- Mittelman, M., & Beckwith, K. (2024). 7 Reasons To Get A Job In Public Health. NurseJournal.org. https://nursejournal.org/healthcare/public-health/reasons-to-get-a-job-in-public-health/NurseJournal.org

- Gage, A. (2021). Guide to a Career in Public Health Research. Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. https://publichealth.tulane.edu/blog/public-health-research/School of Public Health

- Al-Harahsheh, S. T., & Al-Sheyab, N. A. (2024). From decision to destination: factors influencing healthcare students in Qatar to pursue healthcare careers. BMC Medical Education, 24, 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-04636-1

Image Credit: Getty (used under license), Chat GPT