This is an Eval Central archive copy, find the original at evalacademy.com.

Kirkpatrick is probably one of those names/methods you’ve heard about in your evaluation career, but have you ever used it? I’m surprised how many evaluators I talk to that haven’t because I find it pretty useful and straightforward with tonnes of resources to support you.

I love experiential descriptions, that is, reading about how someone else applied a method in a real-world scenario: the ups and downs, the backtracking and lessons learned.

So, having used Kirkpatrick a handful of times on a few initiatives, here is my account of how to use the Kirkpatrick model in your evaluation planning, implementation, and reporting.

What is the Kirkpatrick Model?

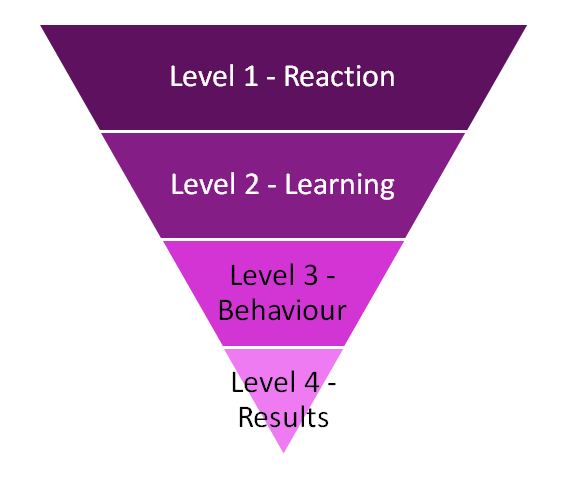

The Kirkpatrick model was originally developed in the 1950s but gained popularity in the 1970s as a way to evaluate training programs. Donald Kirkpatrick proposed 4 levels:

Kirkpatrick can apply to evaluating any type of educational endeavour – where participants or attendees are intended to learn something and implement those learnings.

How do I use the Kirkpatrick Model in Evaluation?

Step 1: Do some basic research.

The model has spawned a website of Kirkpatrick Partners. They host training and events; they have a newsletter, blog and resources to support your use of Kirkpatrick. You can even get certified in using Kirkpatrick. (Disclaimer: I am not certified.) My goal for the rest of this article will be to show you how I’ve actually used Kirkpatrick and some of my thoughts along the way.

Step 2: Incorporate Kirkpatrick in your evaluation plan.

Unless you are exclusively evaluating a training program, I’ve found that Kirkpatrick is often a part of the evaluation plan, but not the only part.

I’ve used Kirkpatrick on an initiative that trained people to facilitate quality improvement in primary care practices. I used Kirkpatrick for the training but had lots of other evaluation questions and data sources for the quality improvement efforts and outcomes in the primary care clinics.

Like RE-AIM, the good news is that Kirkpatrick gives you a solid head start on your training-related evaluation questions.

Your overarching evaluation question might be something like:

To what extent did training prepare people to [make the intended change]?

Or

How effective was the training at improving [desired behaviour]?

From there, use the four levels of the model to ask specific questions or craft outcome statements (See below for a detailed explanation of each level):

-

Level 1: Reaction

-

Level 2: Learning

-

Level 3: Behavior

-

Level 4: Results

Step 3: Reporting

I don’t think I’ve ever used the Kirkpatrick levels explicitly in my reporting. I think most audiences are not interested in the theory of evaluating a training program but are more interested in answering “did the training work?” As I mentioned, Kirkpatrick has usually been only a part of my evaluation planning, so, similarly, reporting on the effectiveness of training is usually only one part of my reporting.

Because Level 1 of Kirkpatrick assesses formative questions about training – things that you could change or adapt before running the training session again, I have often produced formative reports or briefs that summarize just Levels 1 and 2 of Kirkpatrick. This promotes utilization of evaluation results!

Using surveys (or a test!) likely gives you some quantitative data for you to employ your data viz skills on. But keep in mind that it’s not necessary for you to report all of the data you gather. You likely don’t need a graph showing your reader that the participants thought the room was the right temperature. Sometimes less is more and a couple of statements like “Participants found the training environment to be conducive to learning and found the training to be engaging. However, the days were long, and they recommended more breaks.” can cover a lot of your Reaction results. We’ve got lots of resources to help you with your report design.

Sometimes reports, particularly interim reports, are due before you can get to behaviour change or results. This is actually one of the criticisms of Kirkpatrick – that many evaluations will cover Levels 1 and 2 thinking them sufficient but fail to invest the time and resources into ensuring the behaviour changes and outcomes are captured. This is one of the reasons that planning an evaluation concurrently with project design is helpful and can prevent these shortcuts.

How to use the 4 levels of the Kirkpatrick Model

LEVEL 1: REACTION

Reaction is about all those things you think immediately after you’ve attended a session. These are less about what you learned, and more about: Was the trainer effective? Was the environment supportive to learning? Was the day interactive and fun, or didactic and tiring?

Reaction is all of those things that influence learning. They may seem of less importance but contribute a lot to how much a person learns, retains and acts on.

Let’s use a scenario where you are evaluating a training program designed to teach participants how to implement COVID-19 safety protocols in the workplace.

For Reaction, the evaluation is almost entirely content agnostic, so it matters less what the training program is about, and more about the delivery, for example:

The venue was appropriate.

The presenter was engaging.

The training was relevant to my work.

This is almost always captured in a post-training survey, which of course could be paper for in-person events, or QR codes/links for virtual events. It could be emailed out to participants after the session, but we all know that response rates are much better when you carve out 5 minutes at the end of the last session to complete the evaluation.

The learning here is about how you can tweak the delivery of the training. Was the room too cold? Was the presenter about as engaging as Ferris Bueller’s homeroom teacher?

LEVEL 2 – LEARNING

As the name says, level 2 is about assessing what the participant learned. I like to think: Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes. Assessing learning can (and arguably should) touch on each of these. So, your questions might be:

I can explain our COVID-19 safety policies. [knowledge]

I understand why our COVID-19 safety policies are important. [knowledge]

I am confident that I can enforce our COVID-19 safety policies. [attitude]

I learned 3 ways to build buy-in about our COVID-19 safety policies. [skills]

As these examples imply, it’s very common for these questions to be included on a post-workshop survey. I usually embed them with the Reaction survey, so participants fill out one survey after training. I try to keep the total question count under 20, usually Likert Scale, with some opportunity for qualitative feedback.

TIP: If it’s important to you to be able to say that the training was the reason for the results you get, you’ll want to consider a baseline survey – that is, a survey with the same learning questions as the post-training survey, but it’s completed before training. That way, any change that you see can be more strongly linked to the training that they received, as opposed to pre-existing knowledge, skills, or attitudes.

If your training has learning objectives, this is a good place to look for what knowledge, skills or attitudes the program is intended to impact.

Personally, I’ve always lacked confidence in results that come from self-assessed ratings of knowledge, skills, and attitude. We know there are several biases in play – including a tendency to not use the full range of a scale, and to rate yourself positively. One way to mitigate these confounders is to test the learning. Instead of asking for an opinion about what they learned, the post-training survey could be formatted to actually test the learning:

List three COVID-19 safety protocols implemented at your workplace.

Which of the following is a reason why these COVID-19 protocols were selected. [multiple choice]

Describe one way to build buy-in with your staff around COVID-19 policies.

The downside is that not only are these potentially more resource-intense to analyze and report on, but most programs and organizations are worried about the impression it gives to test participants or workshop attendees. We all hate tests, right!? I haven’t had much luck convincing a program to use testing as opposed to a self-rated survey. Let me know if you’ve fared any better!

LEVEL 3 – BEHAVIOUR

Here is where it gets a bit tricky. To measure behaviour you need to have access to the participants after a set amount of time; your participants need an opportunity to put their learning into action.

Assuming you have email addresses or perhaps a reason to bring this group together again, I’ve assessed behaviour change through surveys (yes, surveys again). These surveys are usually sent over email after a pre-determined amount of time. The time interval depends on the learning you are hoping they achieved and the opportunities to implement it. I’ve used anywhere from 4 weeks to 6 months.

In the last [time interval] I have:

Explained why COVID-19 safety protocols are important.

Used techniques learned at training to deal with an individual not wishing to follow COVID-19 safety protocols.

It’s possible that you could re-administer the baseline/post-training survey as a [time interval] follow-up. This would help you to assess retention of learning and may get at some behaviour change too. The difference though is that the assessment of learning was likely opinion-based or in-the-moment, while assessment of behaviour change is retrospective – it’s not about what they have knowledge, attitude or skills to do, or what they intend to do, it’s about what they did do.

Another option is to change your data collection strategy:

-

Observation: can you watch attendees implementing the training?

-

Interviews: can you gather data from people who didn’t attend the training to understand what changes they have seen? Or interview the training attendees to understand what they’ve put into practice (and in what context)

-

Role playing: If you don’t anticipate being able to reach the attendees after a time period, perhaps role playing (and observation) could be a part of the training curriculum. Can attendees demonstrate what they have learned?

-

Evidence of action: perhaps you can access evidence that proves the training resulted in action – maybe participants were asked to write business plans (how many were written?) or were asked to design and implement a communication strategy about COVID-19 policies (was it done?)

In our scenario, observation may look like observing building entrance processes and observing, counting or noting the number of times a COVID-19 policy is explained or enforced. Or, you could survey staff to see how well they understand the COVID-19 policies (assuming their knowledge is a result of the training to select staff). The key to Level 3 is the demonstration of the behaviour.

LEVEL 4: RESULTS

Results brings everything full circle. It drives at the purpose of the training to begin with – what is the impact of the training. In our scenario, the ultimate goal may have been to have staff and patrons compliant with COVID-19 safety protocols. Assessment of Results will be a reflection of this.

# of encounters with non-compliant staff

# of encounters with non-compliant patrons

# of COVID-19 outbreaks at the workplace

Assessment of Results may start to blur the lines with the rest of your evaluation plan. Perhaps the training is part of a larger program that is designed to create a safe environment for staff and patrons, part of which was implementing COVID-19 policies.

Assessment of Results likely requires an even longer time frame than Level 3, Behaviour.

Drawbacks of the Kirkpatrick Model

I’ve found Kirkpatrick to be useful to ensure that evaluation of a training program goes beyond simply measuring reactions, however, the temptation to cut the method short and only measure reaction and learning is common practice.

In perhaps the simplest approach, Kirkpatrick is a survey-heavy method – which relies on adequate response rates and is littered with biases. More rigorous methods to measure the four levels – observation, interviews – are likely more time consuming and resource intensive. It’s a tradeoff. If you go the survey route, here are some tips on how to use Likert scales effectively.

Another common criticism of Kirkpatrick is the assumption of causality. The model takes the stance that good, effective training is a positive experience (Level 1), results in new learning (Level 2), and drives behaviour change (Level 3), which leads to achievement of your desired outcomes (Level 4). It fails to account for the environmental, organizational, and personal contexts that play a role. Whether or not an organization supports the behaviour change or empowers attendees to make change matters, regardless of how fantastic the training was. The further you move through the four levels of Kirkpatrick, the looser the link to causality.

Kirkpatrick Model Return on Investment

At some point, an unofficial 5th Level was added to Kirkpatrick – the Phillips Return on Investment (ROI) model (and sometimes this is not a new level but tacked onto Level 4 – Results). The idea here is that the cost of running training should be absorbed by the positive financial impact on the organizational improvements that come from the training and subsequent behaviour change.

I’ve never actually used the ROI, but there are lots of resources out there to help you.

Other Uses of the Kirkpatrick Model

Here at Eval Academy we often talk about the importance of planning your evaluation right along with program design. Kirkpatrick is no exception. The four levels can offer guidance and perspective on how to actually design a training program from the start. By working backwards, you can ask questions that ensure your training program has the right curriculum and approach to achieve your goals:

-

What are we trying to achieve? (Level 4 – Results)

-

What behaviours need to happen to realize that goal? (Level 3 – Behaviour)

-

What do attendees need to know or learn to implement those behaviours (Level 2 – Learning)

-

How can we package all of this into a high-quality, engaging workshop? (Level 1 – Reaction).

I’ve only ever used Kirkpatrick as a planned-out evaluation approach. It may be trickier to use this model for training that has already happened: you’ll have missed the opportunity for baseline data collection, and importantly, depending on the time that has passed the Reaction results may be less reliable.

I like Kirkpatrick because it’s simple and straightforward. This simplicity is actually one of the main criticisms about it, and its failure to recognize context. However, in my experience, the guidance offered by the four levels helps to shape my thinking about how to evaluate a training program. Because a training program is often only part of a larger initiative, perhaps the lack of context hasn’t been as blatant for me.

I’d love to know your experiences with Kirkpatrick. Have you evaluated all four levels? Have you assessed ROI?

For other real-life accounts of how to use an evaluation methodology, check out our articles on RE-AIM, Developmental Evaluation and Outcome Harvesting.

Sign up for our newsletter

We’ll let you know about our new content, and curate the best new evaluation resources from around the web!

We respect your privacy.

Thank you!

Sources:

Graham, P., Evitts, T. & Thomas-MacLean, R. (2008) “Environmental Scans: How useful are they for primary care research?”. Can Fam Physician. 54(7): 1022-1023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2464800/

Polanin, J.R., Pigott, T.D., Espelage, D.L. & Grotpeter, J.K. (2019) “Best practice guidelines for abstract screening large-evidence systematic reviews and meta-analyses”. Res Synth Methods. 10(3): 330-342. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6771536/