This is an Eval Central archive copy, find the original at rka-learnwithus.com.

By: Emlyn Koster

With climate change and extreme weather frequently in the news and in light of the upcoming UN COP26 Conference, Emlyn taps his geological insights to point out what is often missing from society’s knowledge and which therefore warrants the museum sector’s urgent attention.

Prehistoric Climate Changes

Growing up in the UK where chatting about variable weather is a pastime, I was fascinated to learn about the alternating climates of glacial advance and interglacial retreat stages that occurred during an Ice Age from about 2.5 million years ago to about 12,000 years ago. Whether the UK’s temperate climate is part of an ongoing interglacial stage or in the aftermath of the Ice Age is, as I also learned, unknowable. It is however clear that over the tens, hundreds and thousands of millions of years in Earth history, not only has climate continuously changed, including with other ice ages, but so have the positions of, and ecosystems on, each continent. Homo sapiens are but a blink in the geological eye!

‘The Great Acceleration’ and the ‘Anthropocene’

When I was born in 1950 the human population of 2.5 billion was a third of today’s 7.9 billion and the astronomer Fred Hoyle of Big Bang fame had just anticipated that the first photography of the Earth from space would transform perspectives about human history. How right he would turn out to be!

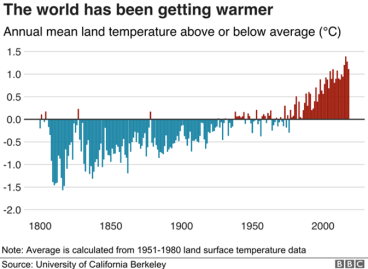

In 1953 the leading climatologist Helmut Landsberg noted in Scientific American: “The big question on Earth is the influence of human activity on the atmosphere. There is some evidence that industrial life has increased the amount of carbon dioxide in the air…”. It would take almost half a century to amass and publicize evidence for human-caused climate change. However, it was only within two decades of Hoyle’s prediction that NASA’s Apollo missions enabled the first color photos of the Earth from space: these revealed the beauty—but also the potential fragility—of our wafer-thin atmosphere. In 2006, the acclaimed film ‘An Inconvenient Truth’ by the former US vice president Al Gore warned of dire consequences from global warming. In 2017, National Geographic issued a supplement with these summary points: “The world is warming… It’s because of us… We’re sure… Ice is melting fast… Weather is getting intense… Wildlife is already hurting… We can do something about it”.

With preliminary versions in 2004 and 2010, in 2015 the Future Earth network affirmed that ‘The Great Acceleration’ of 12 Earth System trends and 12 socio-economic trends began in the mid-20th century: “Human activity, principally the global economic system, is now the prime driver of change in the Earth System—the sum of our planet’s interacting physical, chemical, biological and human processes”. In turn, The Great Acceleration paved the way for the ‘Anthropocene’ which was proposed in 2002 by Nobel laureate Paul Crutzen as a guide to society. The International Science Council recently stated: “For the first time in a relationship spanning 300,000 years, instead of the planet shaping humans, humans are shaping the planet”. I describe the Anthropocene as a much-needed recognition that humanity, the world’s dominant species, has extensively detached itself in a geological nanosecond from the natural state of the Earth System (see Emlyn Koster, 2020. Anthropocene: transdisciplinary shorthand for human disruption of the Earth System. Geoscience Canada, 47:1-2, 59-64).

Climate Change and Extreme Weather

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2015, known as the Paris Agreement, catapulted anthropogenic warming of the atmosphere into a global anxiety. The tipping point to a perilous future, widely stated as a maximum further increase of just 1.5°C (2.7°F) by 2030, frames many profound challenges. Here are three examples. The first surrounds society grasping the massive difference between a seemingly tiny increase in average global temperature over many decades versus local daily and seasonal variations commonly 5-10 times this amount. The second is that a focus on temperature obscures the consequences of sea-level rise in planning for the future of coastal cities (see here, here, and here for examples). The third concerns communities, often poor ones, on deltas and islands where occupation is already or soon will be unfeasible, thereby creating a situation of climate refugees.

What began as the greenhouse effect, the labels for climate change have evolved―global warming, climate crisis, climate emergency, and climate justice. In my geological view, each of these has interpretative limitations. Change?: which direction and how fast? Warming?: what about wetter, stormier and drier trends? Crisis?: should the concern be upgraded to existential, meaning anxiety over the future of human existence? Emergency?: do unforeseen circumstances warrant an immediate response? Justice?: does a moral violation needs a new public policy focus? Today’s talk about climate change uses success-sounding adjectives such as addressing, combatting, fighting and overcoming. But resilience and sustainability are only buzzwords if the reality of many irreversible adverse trends is not confronted. At a recent Youth4Climate summit in Italy, Sweden’s Greta Thunberg again described the efforts of world leaders as too little and too late.

Atmospheric warming is an imperceptibly slow whole-planet process whereas record-breaking weather involves sudden local phenomena. The following examples remind us that headline-making events often lack ultimately more vital wide-angle contexts:

- Superstorm Sandy in October 2012, mostly of sub-hurricane strength, caused an overnight 14-foot surge in New York Harbor and left $70 billion of damage. As restoration proceeded, an opportunity was missed to make known that irreversible sea-level rise by 2100 AD is estimated to be as much as 5 feet which will radically alter shorelines and where people can live and work.

- NOAA rated the snowfall and power cut in Dallas last February as the nation’s costliest winter storm. Dalhart, 440 miles NW of Dallas, received the most snow with 8 inches. It would have been pertinent for the public to also know that Houston had 20 inches on Valentine’s Day in 1895 which was the Texas record until a 26-inch fall near Dallas on December 20-21, 1929.

- Last summer’s drought-caused, record-breaking wildfires in California coincided with New York City’s near-normal monthly temperature averages but these were jolted by two record-breaking one-day (and also record-breaking one-hour) rainfalls: 4.45 inches (1.94 inches) from Tropical storm Henri on August 22 and 8.8 inches (3.1 inches) from Hurricane Ida on September 1.

The Earth System

While dangerous weather grabs public attention, climate change in relation to other major changes in the Earth System is often missing from news coverage. For example, the Earth’s biosphere also functions as a virosphere in which pandemic diseases are exacerbated by climatic change. The American Journal of Managed Care recently stated: “All the negative health outcomes associated with increased heat, pollution exposure, and natural disasters call into question whether existing infrastructure—and particularly health care systems—will be equipped to handle the rising demand for care”. Other consequences of Earth System disruptions include a stunning loss of natural biodiversity and a prediction that about half of the world’s people will likely suffer from water insecurity by 2050.

I wish that, starting in the late 20th century, formal education had included the Earth System as a core subject to equip society to ecologically grasp the interconnectedness and susceptibility of the planet’s controlling forces.

Museum Sector Response

My first career stage as a geologist, and starting a decade ago also as an advocate for the Anthropocene, led to past-present-future links being a frame of reference in my second career stage as a museologist. At the Ontario Science Centre where I was preceded as its director by the renowned J. Tuzo Wilson of seafloor spreading and plate tectonics fame, this institution partnered with the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research in 1996 to convene ‘The Earth System: Geology Lessons for Our Future’ as a pioneering international conference in the public eye.

Museum literature on climate change has been relatively light. In 2015, Fiona Cameron and Brett Neilson co-edited ‘Climate Change and Museum Futures’ and in 2017, Jennifer Newell, Libby Robin and Kirsten Wehner co-edited ‘Curating the Future: Museums, Communities and Climate Change’: Australia deserves a shoutout for these initiatives. In the US, the Journal of Museum Education in March 2020 focused on ‘The Climate is Changing: Why Aren’t Museums?’ and AAM’s Exhibition journal in spring 2021 asked ‘Can Exhibitions Save the Planet?: Tackling Climate Change and Environmental Threats’. A recent issue of Museum & Society, published by the University of Leicester, included a review on Anthropocene-focused exhibitions. Noting that all but nine of the 41 it discovered were/are in art museums, the Danish authors remarked: “… most exhibitions appear to deliberately exclude significant controversies about the Anthropocene and the predicament of the world from their arenas for reflection”. A new international development is The Anthropocene Project based in Toronto.

Last spring, I contributed to the ‘Crisis and Resilience’ issue of AAM’s Exhibition journal with an article advocating for a paradigm shift to illuminate humanity’s pervasive impacts on the Earth System. In this month’s thematic issue of the Informal Learning Review about what the museum sector has learned from the pandemic, my focus is on the continued sidelining of external relevance. In particular, I am concerned that the far-reaching challenges of climate change are understated due to a scarcity of wide-lens and long-view perspectives. I therefore fervently hope that the museum sector responds to the inevitable clarion calls when the UN COP26 Climate Change Conference convenes from October 31 to November 12, 2021 in Glasgow, Scotland.

About the Author

Emlyn Koster, PhD integrates the vantage points of geology, humanism and museology for a holistic past-present-future, nature-and-culture lens. During CEO appointments at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology, Ontario Science Centre, Liberty Science Center with The New York Times and Wall Street Journal profiling his philosophy, and the NC Museum of Natural Sciences, he was 50th anniversary board chair of the Geological Association of Canada, a member of the Committee for the Public Understanding of Science for the AAAS, and the inaugural chair of ICOM’s Anthropocene Working Group. His presentation to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change contributed to the addition of museums as a public education agency in Article 12 of the Paris Agreement and he is involved in UNESCO’s new Language of the Anthropocene project. He welcomes comments and inquiries at [email protected]. You can read his previous blog posts for RK&A here.

The post Geological Context of Climate Change: Implications for Public Understanding and Museum Relevance appeared first on RK&A.