This is an Eval Central archive copy, find the original at medium.com/innovationnetwork.

The act of creating our stories and sharing them with others is a powerful way to better understand our experiences. I realized this in a training on digital storytelling with the Institute for Social Science Research at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

I’ve long used the metaphor of storytelling in my work as an applied researcher and evaluator. The way that we ask questions, conduct our analyses, and represent our results all convey a message or story. As a qualitative and equity-focused evaluator, my aim is to tell the stories that participants in the study want to tell about their own experiences — what meaning they are making, what is important to them, what they want the audience to learn. But it occurred to me while taking this course that we don’t always fully know the message we want to share about our experiences. And the act of creating the story — in written narrative, in visual art, in film or comics or otherwise — actually helps us find our story.

Take, for example, my own digital story on the cocktail of emotions I felt when my mom was diagnosed with cancer. I began writing the story, intending to share a message about the incredible support I received from my community of people. However, through the process of creating my story, I was able to come to the meaning I needed to make about my experience — about the numerous, shifting, and often contradictory emotions I felt through my mom’s diagnosis, treatment, and ultimately recovery.

https://medium.com/media/415589ed81d66316310177aa0c76efae/href

So, what is digital storytelling? How might we use it in learning and evaluation? And what are important ethical issues we evaluators need to consider?

What is digital storytelling and why use it?

Digital storytelling is a method often used in learning and evaluation. It invites participants to identify, create, and produce a 3- to 5-minute video that shares a personal story through an artful combination of narration, images, and sound. The videos produced can then be used to collectively identify and analyze themes to answer learning questions.

Digital storytelling is a form of critical narrative research, which means that participants engage with their stories as a way to critique wider cultural, political, and economic phenomena. It’s easy to see how digital storytelling can also be used as an intervention, education, and advocacy in fields as wide as health/reproductive justice, education, work/labor rights, and more!

Digital storytelling can be used in learning and evaluation many ways. Using Cocktail as an example, the creation of my digital story was a form of data generation itself. As I was writing the narrative, reading it aloud to my peers, and getting feedback from the group, we shared insights about our experiences with the illness of a loved one. When the video was complete, and I showed it to the group, it became an elicitation device — a conversation starter for further discussion on the topic. Our collective of digital stories could even be shared publicly — for example, to advocate for supports to family members and caretakers or to educate health professionals!

How can I use digital storytelling?

Digital storytelling is a flexible method that can be adapted to meet the needs of the participants in the study. For example, if participants are based around the country, the process can be facilitated online or in a hybrid format. If participants have limited digital literacy or technology access, or a more professional appearing video is needed for advocacy purposes, a collaborative process of creating the stories can be used between the researcher and the participant (and maybe even a professional photographer and video editor). And digital storytelling can be used as one of multiple methods in a mixed-methods study.

Just be sure not to simply ‘add-on’ digital storytelling! It’s a time and resource intensive method that requires care to ensure respect and ethical treatment of participants and their stories, and to produce quality stories that generate dialogue and reflection.

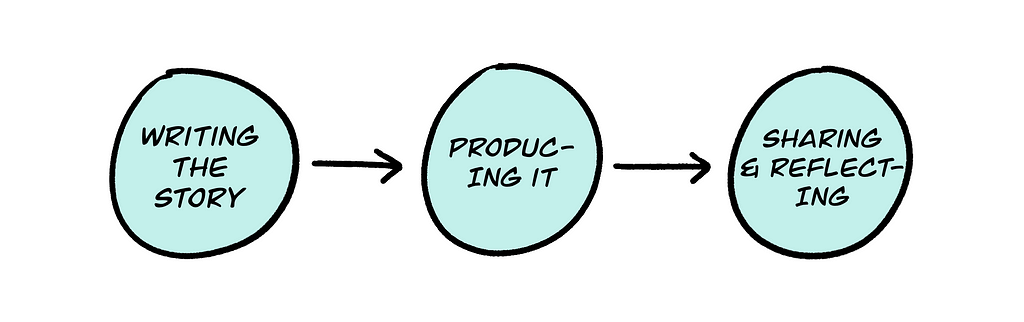

In digital storytelling, there are at least three steps:

- Writing the story. Once a group topic or question is defined (connected to the evaluation and learning project), participants spend time drafting their storyline and narrative. This could be done within a single session or for homework. Some people may prefer to create an outline before writing — for me, I just began free-writing, and that is how I learned what my story would eventually become! The first story circle is held when participants have a first draft. Each participant takes a turn reading aloud their draft and receiving feedback from the group. Facilitators and the group can help participants strengthen their stories by identifying key messages, clarifying language, helping with tone/pacing, knowing where to cut or add content, etc.

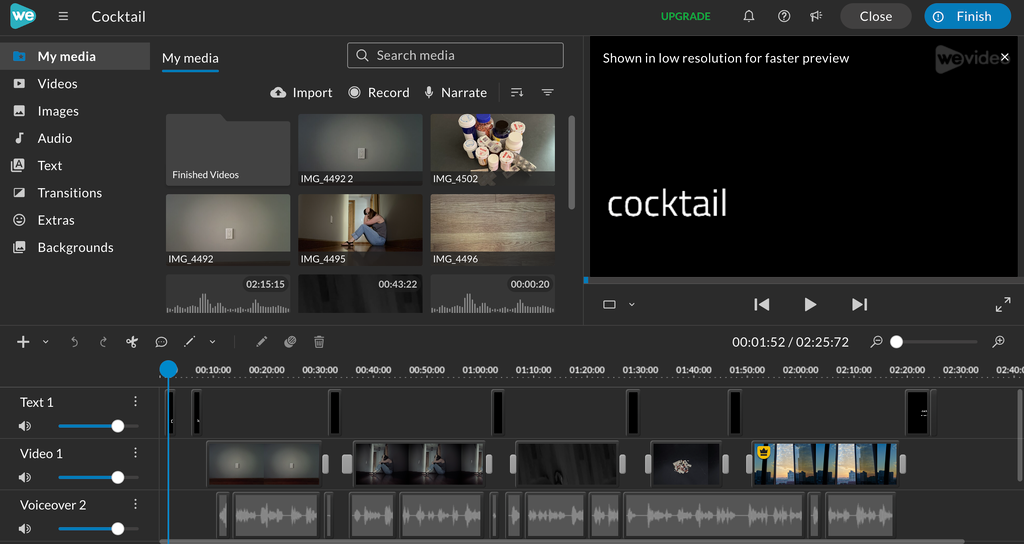

- Producing the story. When stories are finalized, participants then produce their stories. This involves recording the voiceover, creating or finding images, and selecting sound effects. We used an app called WeVideo, which was pretty easy to learn. I recorded my voiceover (it took a few tries and involved hiding in a closet to reduce background noise) and took pictures with my iPhone. I’ve even seen digital stories with hand drawn or illustrated images, which I hope to try next!

- Sharing and reflecting. When all digital stories are complete, the group holds a second story circle to screen the videos. Each participant shows their story to the group. We provided feedback and reflection after each video, but it may be more timely to share 2–3 videos followed by a discussion, and then repeat until all videos are screened. Sharing the stories is the core purpose of digital storytelling, and it is what allows participants to engage critically with their ideas. In a learning and evaluation setting, facilitators could encourage participants to reflect on the conditions leading to the issues identified in the stories, what systemic issues need to change (or are changing), and what factors enable or constrain those changes. The stories could also be a powerful educational or advocacy tool for sharing with organizations, decision-makers, and the wider public.

Ethical issues and power in digital storytelling

Importance of choice. Creating my story, Cocktail, taught me one of the most important ethical considerations in visual and narrative methods — the importance of choice. I have really bad stage fright — even if it’s just reading my own story aloud to a group. Before I read my story during the story circle (which was held online), I told the group that I might turn my camera off if I start to clam up. In other situations, I’ve had to recuse myself from sharing my story personally and have found other ways to share, like asking someone else to read aloud for me. A major ethical consideration is that everyone is being vulnerable in sharing their stories — which may be quite painful. Participants need choices — to read their story aloud, to share it in writing, to ask someone to read it aloud for them, etc.

Telling a personal story that involves others. At the same time, the experience highlighted the important privacy issue of telling my own story, not someone else’s. Throughout the process of creating Cocktail, I had to continually ask myself — whose story am I telling? I made decisions about what I told in my story (and what I left out) because the cancer, the treatment, and all the emotions that went along with that wasn’t my story to tell — it was my mom’s. But I also recognized that as her primary caretaker for a time, I also had a story that needed to be told.

Confidentiality. Another essential ethical consideration in digital storytelling is the timing of obtaining permission to share stories outside of the group (e.g., as educational or advocacy materials). People may participate in the digital storytelling project with full intention to share their stories publicly. But that may change as they move through the process and realize their story is too difficult. Permission to use the stories should only be requested after the stories are finalized and screened within the group, when people have a greater sense of what it feels like to share their story and who they are comfortable with hearing it.

Fortunately for me, the course instructors were not only professionals, but were highly conscientious in ensuring we retained the power over our stories and how they were shared. Staying off camera as I screened my story, I choked up at the overwhelming support I received from my peers and the care and reciprocity they showed. Sharing it with my mom later opened up a conversation we had not had in nearly 10 years since her diagnosis. Creating Cocktail helped me to name and tell my story — of how I felt fear, sadness, and guilt, alongside love, inspiration, and community — a true cocktail of emotions.

How has digital storytelling helped you to find your story? I’d love to hear from you about how you’ve used it (or other participatory visual methods) to find and share your story, or help others do the same!

Finding Our Stories through Digital Storytelling was originally published in InnovationNetwork on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.