This is an Eval Central archive copy, find the original at rka-learnwithus.com.

The next time our senses are filled with an orchestral experience, Emlyn Koster suggests we take away some contemplative lessons for the needs of museums.

A lecture titled ‘The Two Solitudes’ by novelist and chemist C.P. Snow at the University of Cambridge in 1959 became famous. It voiced alarm that the sciences and humanities had become split into two cultures with the division a major handicap to solving global problems. Sadly, this cultural split has grown to include separate associations for science, art, history, site of conscience, and children’s museums with ICOM struggling to negotiate an overarching museum definition. It would be uplifting if 2020’s environmental and societal crises spurred some blurring of these boundaries.

In a 1980 Pulitzer Prize winning book about the composer Bach, the artist Escher and the logician Gödel, the principles of an intelligent approach have long intrigued me. These include responding to situations very flexibly, finding similarities between situations despite differences which may separate them, and synthesizing new concepts by taking old concepts and putting them together in new ways. In a similar vein, the Frameworks Institute reminds us that “metaphors can spark new associations and understandings, putting an issue in a new light and prompting people to rethink their opinions or assumptions” and also “to extend metaphors over time, across contexts, and across networks”.

This spirit of innovative thinking guides me to link the seemingly unconnected worlds of orchestras and museums. An article about the needed evolution of orchestras revived a memory about an up-close experience with an orchestra, itself made possible by a science center program acquainting students with heart surgery in real time. Intrigued? Here are summaries of each element.

Anthony Tommasini, a music critic for The New York Times, opines: “It’s 2021, and we are still debating how to reinvent the orchestra for the 21st century… Now is the moment for orchestras to think big and take chances – yes, even as many players have agreed to salary reductions and administrators are coping with crushing deficits… It starts with creative programming which isn’t just important; it’s everything. I’ve long argued that American orchestras think too much about how they play, and not enough about what they play and why they’re playing it… But perhaps the impediment to creative programming and fresh thinking — including broader racial representation — remains the subscription-series schedule that prevails at all major American orchestras and locks them into standard-issue, week-after-week programs loaded with the classics and sprinkled, at best, with unusual or new choices… Why can’t orchestras be nimble and respond to sudden inspiration, or current events?”.

When Liberty Science Center won ASTC’s Award for Innovation in 2002 for its ‘Live from Surgery’ program, the CT-NJ-NY region of the American Heart Association invited me to join its annual leadership program that featured an immersive two-hour experience with the Stamford Symphony Orchestra. Imagine a ballroom with an orchestra occupying twice its normal space. Next to each musician is a chair for each participant. You choose one of your favorite instruments. The conductor is about to become a facilitator and the symphony is about to become a series of learning modules. Visualize the levels of an orchestra — musicians, section leads, conductor, and the entire orchestra — as correlatives to the employees, section leads, CEO, and the entire organization at your museum. Anticipate that when the interactive session ends, the orchestra plays a whole movement and the conductor guides a lessons-learned and Q&A-styled discussion.

What follows are examples of insights about each level with a caveat that the maximum benefit arises from their seamless integration with a holistic sense of purpose:

- Musicians/employees: giving one’s best to what one decides to pursue… commitment to contribute to a larger result… understanding one’s role in a total context… being energized by a magnificent outcome.

- Sections: different sections have different impacts at different times… ability to peripherally notice everything… become more energized at times of directional change… committing to a conformity of purpose.

- Conductor/CEO: avid student of her/his profession… thinking in many dimensions at the same time… visualizing the journey to the finale… bringing out the best in each player… adept at changing the pace… owning the total acoustical and visual experience.

- Orchestra/Organization: starting only when fully ready… different music, different difficulty… same music played by different orchestras have different outcomes… owning the total sound… the whole rises for applause… the audience inspires the musicians… only a fine orchestra can play with a ballet or opera.

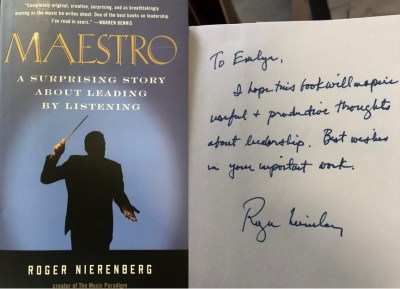

I summarized this powerful experience at the next all-manager forum with members randomly divided in halves and facing each other. Each side took turns voicing positive and negative traits of management which led to an article in the all-staff newsletter. Illustrative excerpts from those lists are, respectively, invested + inclusive + flexible + respectful + supportive and egocentric + close minded + disrespectful + discouraging + discourteous. Roger Nierenberg, the maestro of the Connecticut Symphony Orchestra, has taken his approach to hundreds of organizations in more than a hundred countries and has authored a top-rated leadership book.

Discussing the intent of this blog with a colleague who helps arts, history and science nonprofits to find their next chief executive led to my awareness of a recap by a renowned researcher of managerial practices at Montreal’s McGill University of a day with the conductor of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. The resulting Harvard Business Review article concluded with an insight germane to the museum sector which has been lately besieged by news headlines of directional uncertainties and internal tensions. “Get past the myth of the conductor in complete control and you may learn from this example what a good deal of today’s managing is all about. Not obedience and harmony, but nuances and constraints … Perhaps that is how the manager and the organization can make beautiful music together”.

More than ever, the linked dynamics of organizational propulsion and performance are ripe for reflection and innovation. Museums and symphonies should surely do their utmost to provide society with uplifting experiences. In what ways can exhibitions, programming and facilitated conversations become nimble vehicles for greater public engagement (a question I explore in my upcoming Exhibition article, Paradigm shift to illuminate this disrupted planet)? Preparing this blog also reminded me of a partnership between the NC Museum of Natural Sciences and NC Symphony to celebrate the centenary of NC Parks. Projected images of Appalachian-to-Atlantic scenery above the orchestra were synchronized with Vivaldi’s Four Seasons.

Emlyn Koster, PhD ([email protected]) has been the CEO of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology, Ontario Science Centre, Liberty Science Center, and NC Museum of Natural Sciences. His focus on humanity’s disruption of the Earth System applies reflections about the enablers of museum relevance. Current appointments include ambassador for the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, planning task force chair for the board of the International Big History Association, and adjunct professor in Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at NC State University.

The post Museum propulsion and performance: orchestral insights appeared first on RK&A.