This is an Eval Central archive copy, find the original at freshspectrum.com.

Back in 2006 I was in grad school.

At the time I lived and worked full time in the Maryland suburbs outside of DC. A few times a week, I would take the Metro from the end of the line to downtown DC for evening classes at George Washington University. It was about an hour commute door to door.

By the time class was over it was late in the evening. On the train all around me were people who just looked worn out, coming home from their day jobs far too late. But the thing that struck me the most was what happened when we reached the end of the line.

A few stops before, people started to car hop in order to get to the front of the train (there was always a large group at the doors closest to the exit). And when the train reached Shady Grove station, the doors would open and people would start running.

Being a curious sociologist, I joined them a few times. I wanted to know what they were running towards. Was it to catch a bus or get to a car with a waiting partner or friend?

But for most, it was just a run to the parking garage. This was their first opportunity to take control over their commute. They didn’t get to decide when the trains would show up or when their workday was over, but they could shave a couple of minutes off their commute by being in the metro car nearest the exit and taking a quick jog.

It was times like that when I decided that I never wanted a long daily work commute. I didn’t want to add two hours to my workday, everyday.

The rise of remote work.

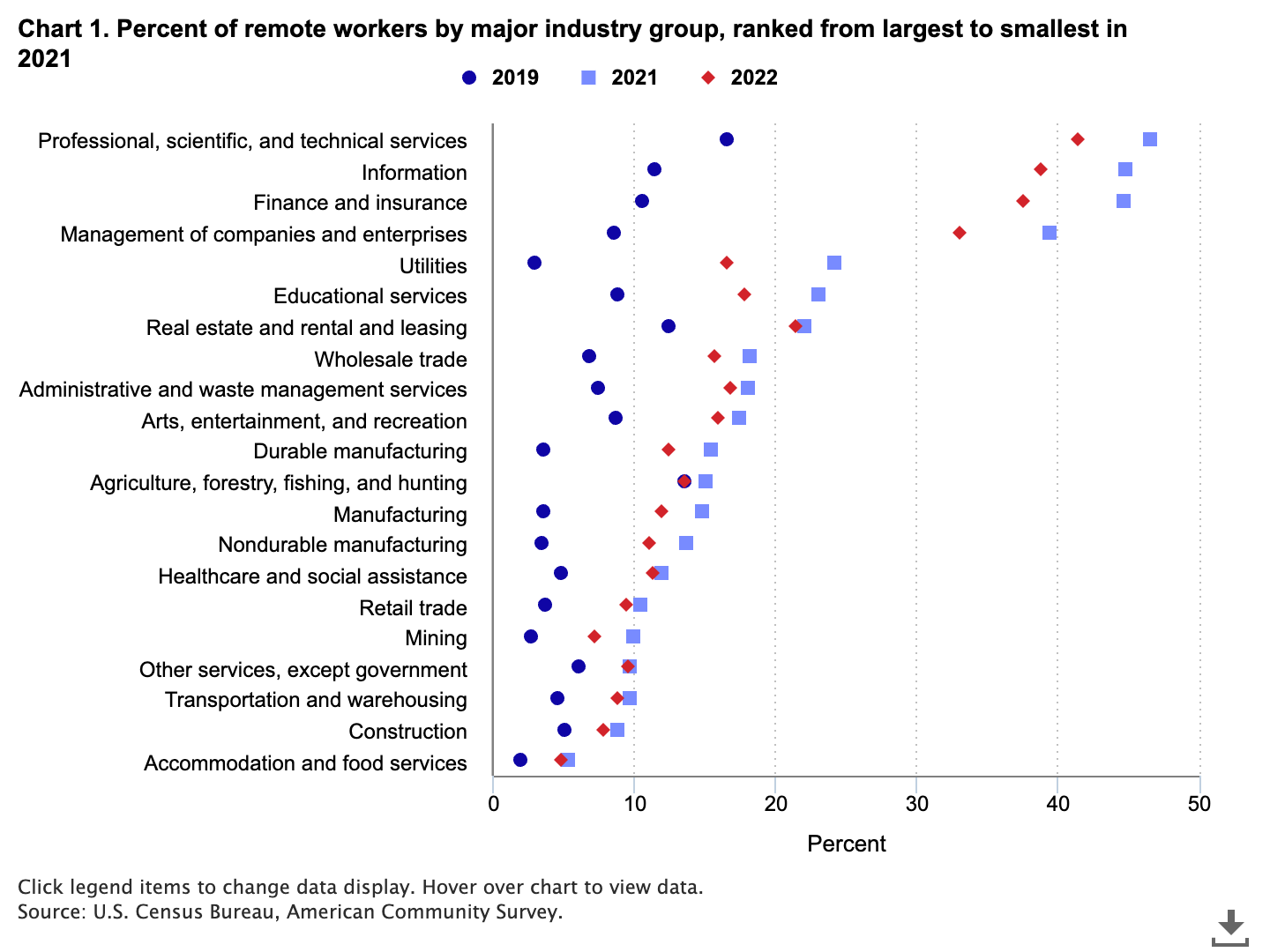

For a lot of people, COVID led to a radical change in the structure of their workplace. In some industries the number of people working remotely more than tripled. The professional, scientific, and technical services and information industries experienced the largest shift.

While some organizations have brought their employees back in-office, I doubt we’ll ever get near the pre-COVID numbers. And as someone who has been remote for most of my career now, I think that’s a good thing.

Lower commutes are better for the environment, improve work-life balance, save money, and can also improve productivity. Remote work also increases the potential workforce and can allow people with disabilities opportunities to work in an environment that better suits their physical or mental needs.

But like everything else, with the benefits we also get some disadvantages.

We find being near coworkers has tradeoffs: proximity increases long-run human capital development at the expense of short-term output.

Source: The Power of Proximity to Coworkers: Training for Tomorrow or Productivity Today?

What really happens when you lose proximity?

Let’s not fool ourselves, there are some advantages to working in an office. Proximity to others creates connections that could lead to advancement. It also creates opportunities for day to day mentorship that don’t generally exist at the same level for remote workers. And according to a recent surgeon general’s report, we are also experiencing a loneliness epidemic.

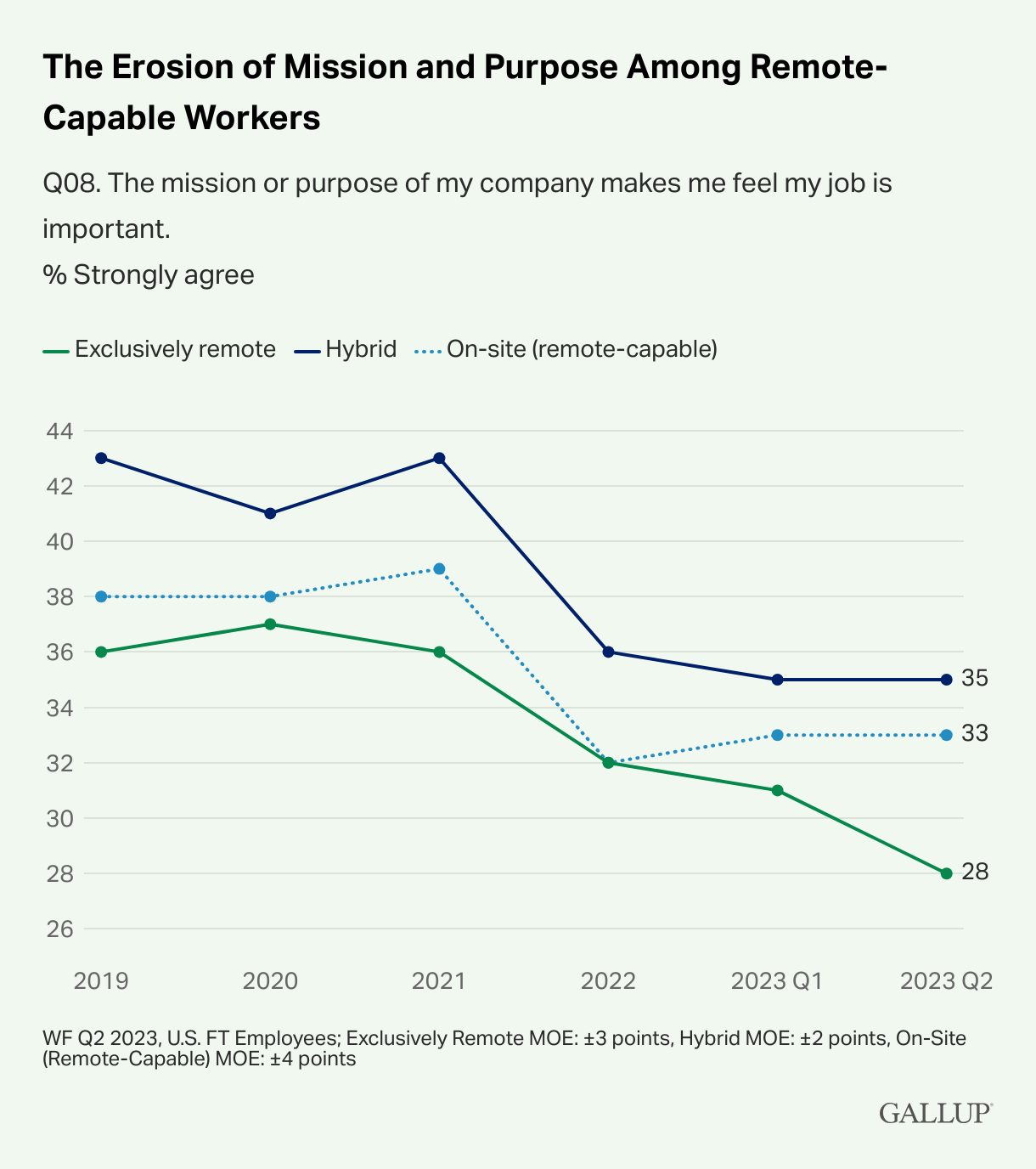

From a company point of view, remote workers tend to be less connected to their mission. And for middle managers, it’s much harder to micromanage…sorry, I should say “monitor,” their team’s productivity.

This has led to a kind of debate about which is better, remote work or office based. But I think that’s a false dichotomy.

If the biggest problem of remote work is a loss of proximity, that doesn’t require you to give up on remote work. You just need to come up with solutions that minimize the negative impact.

And the best way to mitigate a lack of proximity is to build a virtual community.

Tips for building a workplace community in a virtual world.

I’ve been developing virtual Communities of Practice for over a decade. Many of the communities I have worked with have been geographically distributed nationally or internationally. But the same lessons that work for global programs also work for organizations with lots of remote workers.

Here are five of my favorite tips.

1. Start small.

You don’t need a fancy forum, resource library, or sharepoint site to start building community. In fact, you’re better off without it at first. My two favorite community building blocks are an email newsletter and a Zoom account (or Teams, or Webex, etc.).

2. Be consistent.

Communities take time to build. And if you want to develop and facilitate one, you need to show up. Regularly. I suggest meeting at least once a month with video on and sharing a regular newsletter.

3. Leverage your internal expertise.

This is the difference between a lecture series and a CoP. You don’t want just any subject matter expert delivering presentations. Presenters should, for the most part, be members of your community. Having people present, camera on, based on their own areas of expertise creates an introduction that feels genuine, and not forced.

4. Facilitate individual connections.

Communities work better when someone takes on the responsibility of connecting individuals. This can be direct, “hey, you should talk to so and so.” Or this can be indirect by creating a set of individual Q&As, sharing member directories, or making use of breakout groups.

5. Create an advisory group.

Building an advisory group, made up of community members, can help you plan the right sessions and catch any blind spots. Advisory group members will also end up being some of your more committed community members.

Want help building your own Community of Practice?

As a consultant I help organizations design, develop, and facilitate modern Communities of Practice. So if you would like a little support (or a lot of support) the best place to start is with a conversation. Click here to schedule your free 30 minute consultation.