This is an Eval Central archive copy, find the original at medium.com/innovationnetwork.

Part of our role as evaluators is to communicate learnings so that people can easily understand and translate those learnings for their own work — in many ways, we are failing in this role. As I was working on the Equitable Communications Guide (published last year), I became more aware of the ways we as evaluators are often ableist and exclusionary. It’s human nature to categorize, even other humans, creating shortcuts to determine what — or who — is familiar and safe to be around. But this natural behavior creates “in groups” and “out groups,” and leaves us unaware of the realities outside our own groups. I’ve come to believe the term “mental model” is another way we perpetuate an “in group,” and creates exclusion when we have the opportunity to be more inclusive.

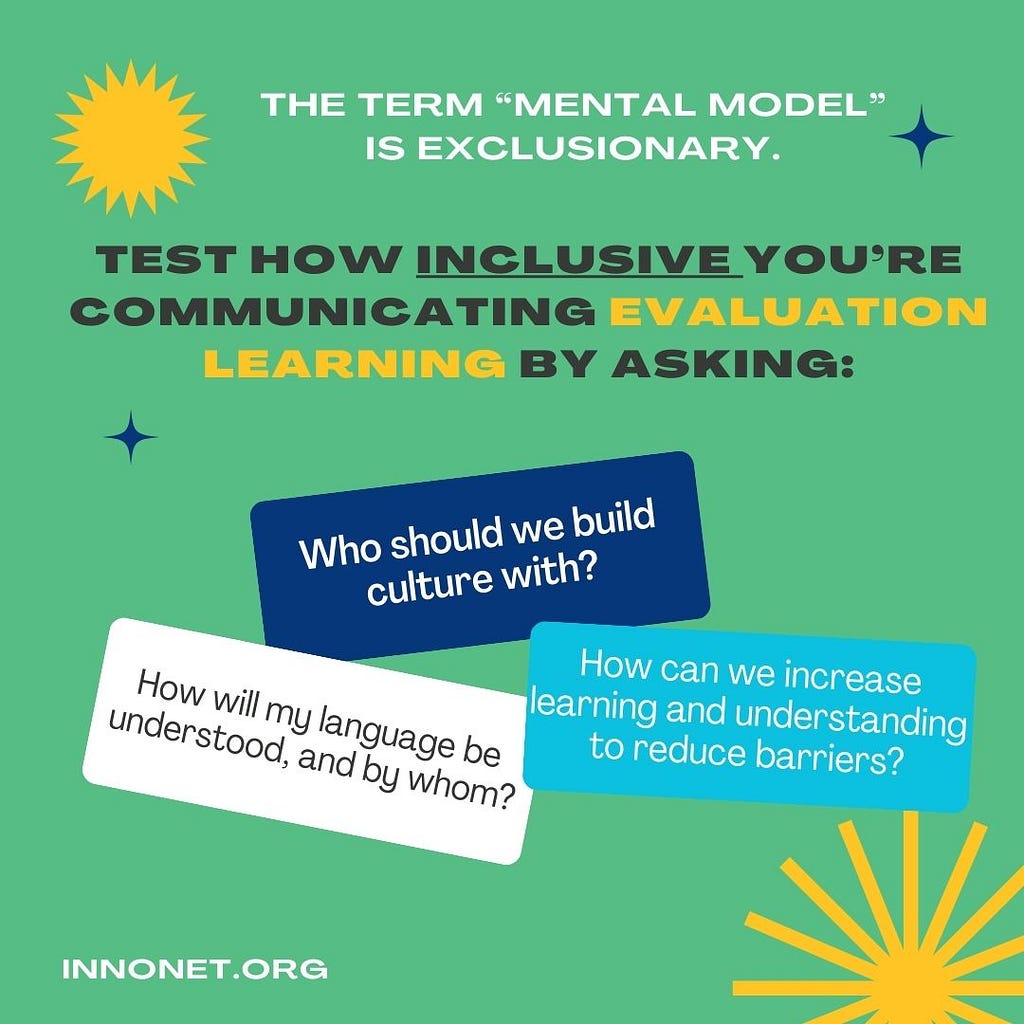

I’ve come to believe the term “mental model” is another way we perpetuate an “in group,” and creates exclusion when we have the opportunity to be more inclusive.

This exclusion is not intentional of course. “Mental model” is a term that has come to mean “the internal representations of external reality that individuals use to understand, interpret, and navigate the world around them. They consist of a set of beliefs, generalizations, and assumptions that make up our worldview” [1]. It was coined by psychologist Kenneth Craik in 1943 [2], and gained traction in the 1980s when Johnson-Laird connected the idea to semantic reasoning in psychology. The term became applicable beyond psychology when Peter Senge began using the concept in the business and management context in the 1990s [3].

I’m not sure when “mental model” entered the evaluation space, but I’ve seen increasing use of it in our field, including in publications and by influential thought leaders in our field. I remember attending an AEA session in 2023 where a panelist shared her excitement upon discovering the term. “Mental model” revealed a nuance in meaning for her that other terms weren’t capturing — it was the best way to describe what she wanted to say.

Language does have an important role in the micro cultures we create, such as within the evaluation field. Edgar Schein’s framework defines the forces that govern workplace culture. He describes shared language, including stories, jargon, and sayings, as “verbal artifacts” of a culture that supports belonging and camaraderie among colleagues [4].

I don’t want to discount the benefits the term “mental model” has brought to the people who use it. But I do want to examine what we lose by using the term.

The term “mental model” creates an in group of people who know what this term means.

The term “mental model” creates an in group of people who know what this term means. And the people who know what it means are typically advanced degree professionals in evaluation and academia. For those who use it in the evaluation space, the term builds culture, connection, and a feeling of belonging with others who are interested in the same ideas. But it also creates outsiders, who are often the people who have the most to learn from our evaluative work.

It’s true that we use many terms that nonprofessional evaluators don’t understand. I would argue that many of these are necessary, but that “mental model” is not one of those. For example, some people outside of evaluation and research haven’t heard of a “theory if change,” don’t understand what a “sample” means, and could not explain data “coding.” But these words are all industry terms that name something specific and exist to create necessary language for something we do that is unique to our industry. The difference between our industry-specific terms with the term “mental model” is that it doesn’t name something new, it adds nuance to commonly used terms that are already widely understood. Nuance that may not be necessary for an audience who can benefit from our knowledge.

We are excluding people who are outside of the evaluation field who can benefit from our evaluation knowledge.

As a comparison — dentists diagnose cavities. As patients, we understand the important industry term “cavity,” but we rarely understand the nuance that is less relevant to our daily lives, like the type of cavity (smooth, fissure, or root) or what class of cavity (there are six). These classifications are vital to a dentist determining the right treatment, yet a good dentist will use “cavity” when speaking with patients and clearly describe the problem without using jargon.

When we use “mental model,” we are saying “Class VI Fissure” without using clear language, excluding people who are outside of the evaluation field who can benefit from our evaluation knowledge. We may lose nuance, but increase understanding when we choose language that more people are familiar with. “Worldview” and “perspective” are excellent alternatives to “mental model” that have broader use and acceptance.

To communicate equitably, we should strive for inclusive language with the most direct route to comprehension.

To communicate equitably, we should strive for inclusive language with the most direct route to comprehension. We should seek to build community outside of our evaluation in-group, and invite more people to the knowledge we have the privilege of gaining as evaluators. To ensure we are inclusive, we should ask:

– Who should we build culture with?

– How will my language be understood, and by whom?

– How can we increase learning and understanding and reduce barriers?

Is using the term “mental model” worth excluding people, and excluding broader understanding of our learning and insight? In my practice, the answer is no.

Why to Stop Saying “Mental Model” was originally published in InnovationNetwork on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.